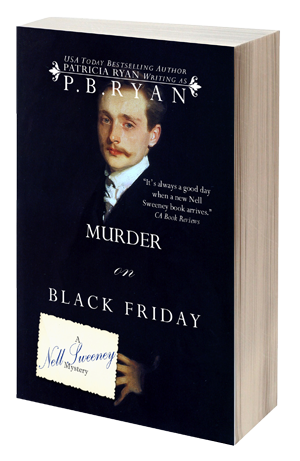

Excerpt: Murder on Black Friday

Book 4: Nell Sweeney Mysteries

September 25, 1869: Boston

“Are you expecting someone, Mrs. Hewitt?” Nell Sweeney scooped up a spatula full of warm hide glue and spread it on the freshly stretched canvas propped on her easel.

“A bit early in the morning for callers, I should think.” Wheeling her Merlin chair away from her work in progress, a still life of autumn fruit, Viola Hewitt rummaged amid the paint tubes and turpentine-soaked rags on her worktable. “Where in Hades did I put that watch?”

“I’ll get it, Nana.” Little Gracie Hewitt leapt up from the solarium’s slate floor, on which she was chalking the shifting patterns of sunlight streaming in through the tall, leaded glass windows. Clicking open the little diamond-encrusted pocket watch, she offered it to Viola.

Nell, ever the governess, said, “Can you read the time yourself, Gracie?”

Gracie studied the watch intently.

“Where’s the little hand?” Nell asked as she ran the spatula down the drum-tight linen, skimming off the surplus glue.

“At the eight.”

“And the big hand?”

“At the thwee.”

“Three,” Nell gently corrected; they’d been working on her diction. “So that would mean it’s…?”

“Eight, um…” Gracie screwed up her face in concentration. “Thirty?”

“Eight-fifteen,” Nell said.

“Good try, though,” Viola said in her throaty, British-inflected voice as she mixed a dab of ultramarine into the rose madder on her palette. “Nell, dear, what makes you think I’d be expecting someone at this hour? I’m not at home for callers till ten–and I’m hardly dressed for company.” Like Nell, she wore a gray, paint-spattered smocked tunic over her morning dress.

“Someone knocked at the front door,” Nell said she dipped her spatula back in the glue pot, which was snugged into a pan of hot water. “You didn’t hear it?”

“My ears are only there for show nowadays,” Viola said as footsteps shuffled toward them along the long, marble-floored central hall.

Hodges, the Hewitts’ elderly butler, appeared in the open doorway looking oddly hesitant. “So sorry to interrupt, Mrs. Hewitt. Your son is here to see you.”

“Harry? Really?” Viola’s roguish and dissolute middle son had spent the past year and a half in self-imposed exile from the family’s Tremont Street mansion. As far as Nell knew, Viola hadn’t even seen him since June, when his engagement to Cecilia Pratt was announced over dinner at her parents’ home. Of Viola’s three living sons, twenty-two-year-old Martin was the only one still at home–and the only one who still enjoyed cordial relations with his parents.

Hodges said, “It’s not Mr. Harry, ma’am. It’s…Dr. Hewitt. William.”

“Will?” Viola gaped at Hodges, and then at Nell, who shared her astonishment.

It had been almost six years since the Hewitts’ eldest son had set foot in this house. Even during his youth, Will had been more of an occasional visitor than a member of the family, having been shunted off to England when he was Gracie’s age to be reared by indifferent relatives and educated in a succession of boarding schools–thus inaugurating three decades of semi-estrangement from Viola and August Hewitt. Will’s coolness toward his mother had begun to thaw a bit this past spring, before the Hewitts and their staff left for their summer home on Cape Cod, and Will for Europe. As for the stern and venerable August, Nell doubted he and Will would ever exchange a civil word again.

Nell listened to Will’s approaching footsteps as she buttered the canvas with glue and scraped away the excess, thinking she would have known his unhurried, long-legged stride anywhere. She tried to draw a deep breath, but her stays hindered that, which made her feel like a ninny for wearing so many pointless layers of clothing under this blasted smock frock that hid everything anyway, making her look like some great, fat, ugly, repulsive farmwife. It didn’t help that her hastily coiled chignon was held in place with two paint-crusted hog’s hair filbert brushes.

The footsteps stopped.

Nell turned, spatula dripping, to find Will standing just outside the doorway in a handsome black morning coat and fawn trousers, top hat in hand, inky hair smartly combed, smiling at her. She’d seen him only twice since she’d been back from the Cape, all too briefly both times. In the past, he would sometimes join Nell and Gracie for their afternoon outings in the Common and Public Garden–when he was in Boston, and not off playing faro and vingt-et-un for outrageous stakes in some exotic and dangerous city. But now that he was teaching, he had a good deal less free time during the day.

“Mother.” He bowed to Viola, straightening only partially as he ducked into the sun-washed solarium. “What a remarkable display of industry for so early in the morning.”

“Almost unseemly, I know,” Viola said.

“My thoughts precisely.”

Every time Nell saw Will and his mother together, she was struck by their similarities, not just in appearance–the height, the dramatic coloring–but in their manner of speech. Although Will’s accent was stronger than that of Viola, who’d spent the past thirty-two years in Boston, they both spoke with the refined nuances of the British upper classes. Even when Will had been an embittered, soul-weary opium addict, he’d always sounded like a gentleman–and usually acted like one, too, despite his best efforts to turn his back on the “hollow, gold-plated world” he’d been born into.

“Nell.” He bowed, smiling that coolly intimate smile that he never seemed to use with anyone else.

“Good to see you, Will.”

“Uncle Will!” Gracie launched herself into Will’s arms as he crouched to gather her up.

He groaned with mock effort as he lifted her high, taking care not to let her head bump the ceiling. “By Jove, you’re taller every time I see you–a raven-haired beanpole, just like your nana.” To Viola, he said, “She’s the spitting image of you.”

Gracie made an exaggeratedly bemused face, as if “Uncle Will” had said something ludicrous. “Nana’s not my weal mommy. She picked me out special ’cause she always wanted a little girl, and she never had one, but now she has me. I’m dopted, wight, Nana?”

“Adopted. Yes, that’s right, darling.” Viola met her son’s eyes for a weighty moment before looking away to set her palette on the worktable.

Will, suddenly sobered, kissed the child’s forehead and set her down. “I knew that. I was just teasing.”

He glanced at Nell, who offered a weak smile as she knelt to wipe up the glue that had dripped onto the floor from her neglected spatula. Setting his hat aside, Will hitched up his trousers and crouched down, a bit stiffly because of the old bullet wound in his leg. “Here.” He took the rag from her hand and set about cleaning up the mess himself. “Watching you scrub a floor is like seeing a lovely little mourning dove on a trash heap.”

Having always thought of mourning doves as gray and ordinary, Nell wasn’t entirely sure how to take that.

“Uncle Will, guess what?” Gracie asked excitedly. “Tomowwow’s my birthday, and the next day I get to go on a twain and a steamship.”

“You do?”

“The twain goes to, um…” The child looked to her nana for a prompt.

“Bristol, Rhode Island,” Viola said.

“Bwistol, Wode Island, only it’s not weally an island, and then we get on a steamship called the Pwovidence that looks like a palace inside.”

“The Providence, eh? You’re going to New York, then, I take it?”

Viola said, “Your father and I are taking Gracie on a birthday visit to your Great-Aunt Hewitt in Gramercy Park. We’ll be gone a week.”

“Really?” There was a note of genuine surprise in Will’s response, and Nell knew why. August Hewitt had never made any secret of the fact that he found Gracie’s presence in his home as vexing as that of the upstart Irish nursery governess entrusted with her care. On his instructions, the child took all her meals, except for holiday dinners, with Nell in the third floor nursery, and he never spent very long in the same room with Gracie before ordering her removed. For him to consent to a weeklong trip with the child was remarkable.

Viola said, “Aunt Hewitt commanded us to visit when she found out Gracie was turning five. She wrote and said she was afraid she’d die without ever having met her. I wrote back that I was more than willing, that it was your father she had to convince. She sent him a letter. I didn’t read it, but that evening over supper, he suggested the trip. We’re bringing Nurse Parrish along to look after Gracie.”

“Nurse Parrish?” Will said dubiously. “She must be ninety by now. Can she still travel?”

“She’s eighty-three, and she tells me she’s looking forward to the trip. She loves New York, and she hasn’t been there in years.”

Taking Nell along would, of course, have been out of the question. Mr. Hewitt loathed her as deeply as he did Will. It was only his indulgent love for his wife, and Viola’s own steely resolve, that had permitted Nell to remain with the family as long as she had.

“You must draw pictures of the things you see in New York,” Will told Gracie, “so you can show them to me when you get back. I know you like to draw, like Nana and Miss Sweeney.” Pointing to the crude but oddly cheerful design chalked onto the floor amid the forest of easels, Will said, “This is your handiwork, is it not?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Yes, sir,” Nell softly corrected.

“Yes, sir,” Gracie echoed. “I dwew the morning sunshine, ’cause Miseeney says she misses it when it goes away.”

“How very thoughtful of you,” Will praised as he awkwardly gained his feet.

“And how very thoughtful of you,” his mother told him, “to pay a call at the house. You don’t know what it means to me, Will. Your, uh, your father is at his office, by the way, so…” She glanced at Gracie, who was sprawled on the floor again, chalk in hand. “You know. You needn’t worry that there will be any…unpleasantness.”

“He’s working?” Will asked. “On a Saturday?”

“He’s worse than ever,” Viola said with a slightly weary, smile. “Six days a week, he’s at India Wharf by dawn.” August Hewitt’s dedication to the shipping empire founded by his great-great grandfather was legendary among his fellow “codfish aristocrats.”

“I wish I could claim that my visit was prompted by mere thoughtfulness,” Will said. “The fact is, I’ve something rather distressing to report.”

“Oh, dear.” Viola’s smile waned. “I can’t say I’m eager for any more bad news, after that frightful gold business yesterday. Your father knows men who lost their entire…” Looking up sharply, she said, “You’re all right, aren’t you, Will? You didn’t…?”

“Good Lord, no. I’ve never invested in gold.” Will kept his considerable gambling swag in the weather-beaten alligator satchel Viola had gifted him with upon his graduation from medical school at the University of Edinburgh. “No, I came through yesterday quite unscathed, but as you’ve pointed out, the same can’t be said for everyone.” He looked around, rubbing his neck. “I say, are there any chairs in this room, or…?”

“Here.” Nell pulled out a paint-speckled kitchen chair that had been tucked under a table. “It’s safe to sit on. The paint’s dry.”

Will sat and crossed his legs, lifting the bad one over the good one with his hands. “Nell must have told you I accepted a position as adjunct professor at Harvard–just for the autumn term. I’m really not cut out for that life anymore, but Isaac Foster talked me into it, and it affords me the opportunity to do some rather diverting research. Foster was named assistant dean of the medical school over the summer–did you know?”

Viola nodded. “Winnie Pratt told me about that–crowed about it–when she wrote to announce Dr. Foster’s engagement to her daughter Emily while I was on the Cape.”

“I’m teaching medical jurisprudence,” Will said. “What Professor Cuthbert at Edinburgh used to call forensic studies–the legal applications of medicine. One of my conditions when I accepted the position was the right to conduct post-mortems on any good corpses that end up in the morgue at Massachusetts General.”

“Good corpses?” Viola said dubiously.

Will cast a little half-smile toward Nell, as if to say, You understand.

“There are good corpses,” said Nell, who’d assisted at some truly fascinating autopsies during the four years in which she’d been trained in nursing by Dr. Greaves before coming to work for the Hewitts. “Someone whose death was violent or unexplained can be very interesting to dissect, if one knows what to look for.”

“I thought the county coroners handled that sort of thing,” Viola said.

“Yes,” Will said, “but they’re all laymen, so they have to pay private surgeons to perform the actual autopsies–when they bother with them. I’m saving them a bit of trouble and expense by taking on the chewier cases myself. In any event, yesterday evening, two bodies were brought to the morgue, the deaths apparently unrelated, but with one thing in common. Both men had evidently taken their own lives.” He paused, then added, “One of those men, I’m sorry to say, was Noah Bassett.”

“No.” Viola sank back in her wheelchair, looking stricken. “Oh, Will, no. Not Noah.”

Will glanced at Nell as if for support in being the bearer of such grim tidings. She managed a reassuring look despite her own shock and dismay, having grown quite fond of Mr. Bassett herself from when he and his daughters would visit the house.

“I was dreading having to give you this news.” Uncrossing his legs, Will leaned forward to rest his elbows on his knees. “I know how much your friendship with the Bassetts means to you. I’d wanted to tell you myself before you read about it in the morning paper.”

“Thank you, Will.” Viola shook her head listlessly. “I wish I could say it comes as a shock that Noah would…do something like that, but given the way his life’s gone these past few years… Was he ruined in the gold crash, do you know?”

“One can only assume so, but I’ll need to find out for sure. To draw a reliable conclusion about a death like this, one must examine not only the victim’s body, but his life–his state of mind, his situation, the circumstances in which he died. Which is partly why I’m here, to help fill in those blanks–although the evidence so far does indicate that Mr. Bassett died by his own hand.”

“How…” Viola hesitated, as if she wasn’t sure she really wanted to know. “How did he…?”

“He apparently locked himself in his bedroom, filled his bathtub with warm water, and opened both radial arteries with–“

“Radial…?”

“He cut his wrists,” Nell said.

“With a pen knife,” Will added. “His death resulted from massive blood loss.”

Viola closed her eyes, color leaching from face. “Noah, Noah… He was my age exactly, fifty-nine. Our birthdays were only a week apart.”

“His daughter found him,” Will said.

“Which one?” his mother asked. “He’s got two, and they both live with him.”

“Her name is Miriam.”

“She’s the eldest,” Viola said. “About your age, I suspect, mid-thirties or so.”

“A spinster?” Will asked.

“Not for long. She’s engaged to a professor at Harvard Divinity School–Martin’s favorite professor, as a matter of fact, the Reverend John Tanner.”

“Really?” Nell said. “I always sort of assumed Dr. Tanner was married–but perhaps that’s just because he’s a clergyman.”

“You know him?” Will asked.

Nell nodded. “Martin’s had him over to the house a few times. He seems like a pleasant fellow.”

“Your father can’t bear him, because he’s a Unitarian,” Viola said, “but I agree with Nell. He seems like a good man, and I think he’s the right sort for Miriam. She’s the type one would never suspect of having been born into great wealth. She reminded me of Noah in that way–of Noah as he used to be. Mature, pragmatic, capable… I’m glad she’s the one who found him, and not Becky.”

“Becky’s the younger sister?” Will asked.

“Yes. Rebecca, but everyone calls her Becky. Just turned nineteen, I believe, but she seems younger. One of those chatty, chipper young girls, you know? But quite likeable, really.”

“There are just the two daughters?” Will asked. “That’s quite a gap between children.”

“They had a son in between–Tommy. He died in the war. And Lucy, Noah’s wife–his late wife–suffered a number of sad events during those years, as well.”

“Sad events?” Will asked.

“Miscarriages,” Nell said.

“It was heartbreaking,” Viola said, “watching her lose all those babies. Lucy Bassett was the warmest, most generous and patient soul I’ve ever known–the perfect wife for Noah. All she ever wanted was to have a houseful of children to love and take care of. She had no problem having Miriam, but then it took her so long to carry a second child to full term. Miriam was eleven when Tommy was born. There was at least one other disappointment after that. I know Noah wanted her to stop trying for more children, because it was just too upsetting for her, and she wasn’t that young anymore, but then along came Becky. ‘My little gift from God,’ Lucy called her. Unfortunately, her health started deteriorating after that. She died of cancer when Becky was just three years old.”

“How did her husband react to her death?” Will asked.

“Oh, he was devastated. It tore him apart. He was a wonderful man, you know, but far too easily bruised for his own good.” Viola’s voice was hoarser than usual; her eyes shone wetly. She groped under the cuff of her smock for the handkerchief she kept tucked in her dress sleeve.

Will shook his out and handed it to her.

Dabbing her eyes, Viola said, “Poor Noah, he was never the same after that. He was quite a large man, you know–tall and big-boned, and always, well, a bit on the stocky side, with these great, bushy mutton-chop whiskers. I used to think of him as a giant, kindly bear. He was a very popular fellow, the kind of warm-hearted man everyone loved. But after he lost Lucy, he became more like a…well, one of those big, shambling dogs that always looks a bit sad and confused. Then, when he lost Tommy right before the war ended, he just seemed to…gradually collapse. He retreated into himself, neglected his appearance, stopped calling on his friends. We paid a New Year’s Day call on him this year, Nell and Gracie and Martin and I. Miriam told us he was still in bed–at one-thirty in the afternoon.”

Will said, “I’ll need to speak to his daughters before I can confidently label it a suicide, but if he’d been mentally depressed for a number of years, as you suggest, that would make it all the more likely that a major financial loss might send him over the edge. Mr. Munro’s case is a bit woollier, I’m afraid.”

“Philip Munro?” Viola asked.

Will nodded. “He was the other man I autopsied yesterday.”

“Oh, my word,” Viola said. “He’s so young. “Was so young.”

“Thirty-nine,” Will said. “You knew him, obviously.”

“We all knew him, everyone. Well, everyone in a certain circle.” The circle of Boston’s Brahmin elite, she meant. It was a tight-knit, exclusive little cosmos unto itself, governed by a rigid code of conduct. She said, “Your brother Harry knew him particularly well. They’d become bosom friends in the past year or so.”

“Really?” Will said. “Munro’s more than ten years older than Harry.”

“They were both bachelors, though, and of like temperament, and after Harry moved out of the house, they lived only two or three blocks apart in the Back Bay. And if you want to know the truth, I do believe there was a fair amount of hero worship involved. I’m told Harry idolized Mr. Munro.”

“Even more than he idolizes himself?” Will said aridly.

Viola said, “Actually, yes. Mr. Munro was older and even richer than Harry, a self-made, charismatic man about town. Handsome, roguish, athletic…and something of a rakehell, which must have appealed enormously to Harry.” She shook her head. “It’s just so hard to believe. Philip Munro, of all people.”

“Why does it surprise you so?” Will asked.

“Well, he was…Philip Munro. He was just so…on top of it all, so confident–to the point of arrogance, but one can hardly blame him. He was indecently rich, you know. New money–his father had been a schoolteacher in Brookline–but it was money nonetheless, and in this city, that counts for something.”

“So does lineage,” Will said. “Was he truly accepted by the old guard? Did they let him into the Somerset Club? Did they whisper behind his back?”

“Well…” Viola appeared to ponder the question. “Boston isn’t quite as bad as New York, where you’ve got to be a sixth generation Knickerbocker before they’ll even acknowledge one’s existence. Still, there is a caste system here, and although they admire achievements, especially as regards business endeavors, I’m afraid it’s pedigree that counts in the long run.”

It was always they when Viola discussed Boston society, not we. Having retained many of the boheme ideals of her youth, she’d never truly felt at home in her husband’s world of wealth and propriety.

“No, they never invited him into the Somerset,” Viola continued. “And there were whispers, to be sure, but they weren’t so much about his lack of breeding as about, well, the way he conducted his private life–although the one was generally blamed for the other.”

“If Munro’s private life was anything like Harry’s,” Will observed, “I don’t doubt he raised a few eyebrows. Especially given his age. Thirty-nine might seem young to you, ma’am, but it strikes me as a bit long in the tooth to be larking about with reprobates like Harry on drunken night sprees and the like.”

“Philip Munro was a firebrand, there’s no denying that,” Viola said. “They say he brought that same sense of daring and recklessness to his business transactions, did insanely risky things, yet he always came out on top.”

“What sort of business did he engage in?” Will asked.

“I believe it had to do with the stock market, mostly, though I confess I’m at a loss as to exactly what it was he did. Those sorts of things–stocks, commodities–they’re utterly foreign to me. Your father disapproved of him, said he wasn’t so much a businessman as a gambler. What was it he called him? A ‘nouveau riche raider.’ Oh, and he had connections, you know–friends in New York and Washington, important, powerful men, the kind who share information and help one another out. I understand he dined with President Grant, he and some of his financier friends, when the president came to Boston in June for the Peace Jubilee.”

“That can’t have hurt his business,” Will said.

“Oh, he made buckets of money, and his money made more money. Before long the men here in Boston who’d once snickered at him were lining up at his door for advice on how to do the same thing–not your father, of course, but most of the others. His back door, mind you. No respectable gentleman wanted to be connected too closely to the likes of Philip Munro.”

“Mustn’t be seen paying a call on the man,” Will said, “but they didn’t mind handing over their purses?”

Viola smiled. “Yes, but you see, they handed them over empty and got them back full. Mr. Munro wasn’t afraid of money, or vaguely ashamed of it, the way the rest of them are. He bought and sold and connived and speculated as if it were all a game and he could invent and reinvent the rules as he went along.”

“Did he always win?” Will asked.

“Often enough to keep some of the most powerful men in Boston in his thrall.”

“Was he in league with those Goldbugs, do you know?” Will meant Jay Gould and his cronies, whose greedy machinations had forced President Grant to sell off some of the government’s supply in order to lower its price, resulting in yesterday’s devastating market collapse. Gould was by far the most notorious Wall Street raider alive, and now the most loathed. Anyone who’d owned gold at noon yesterday, when its value plummeted–and that was a great many people–took a cruel beating. Thousands of investors were left in complete financial ruin.

Viola said, “I don’t think anyone was ever really privy to what he bought and sold, just that he made mountains of money doing it. If he was a gold speculator, let’s hope he didn’t talk Harry into getting involved in it.”

“You didn’t mind Harry befriending a blighter like Munro?” Will asked.

“That question,” Viola said with a sardonic smile, “implies that I enjoy some measure of influence over what Harry does and with whom. Of course I disapproved of Mr. Munro–not because of his background, needless to say, but because of his behavior. But he’s the reason your brother started playing cricket at the Peabody Club up in Cambridge, which I was actually quite pleased about. I thought it might, oh you know, be good for Harry to get a bit of fresh air and exercise. I’m surprised he never asked you to come along.”

Choosing his words with obvious care, Will said, “Harry and I don’t see very much of each other.” Not since the thorough beating Will dealt his brother last year after learning of Harry’s absinthe-fueled attempt to force himself on Nell–something Viola would never, God willing, find out about.

“Harry will take this very hard,” Viola murmured, staring out the window at her little English-style garden, all tangled and leggy, the way it got every year at the end of the summer, no matter how hard Viola worked on it. “How did he die?” she asked without turning from the window.

“That’s debatable, as far as I’m concerned. He was found on the front steps of his house on Marlborough Street, beneath the open window of his office on the fourth floor. It seems fairly clear that he fell that distance, but there are no witnesses. He’s got an unwed sister who lives with him, but I’m told she was napping when it happened, and none of the servants actually saw him fall. He was pretty badly smashed up, but in a way that makes me doubt that he died from the fall itself.”

“I wan out of chalk.” Gracie was standing over her artwork, a stub of chalk in her hand, squirming in a way that instantly put Nell on the alert. “Can I have some more?”

Viola, who was within grabbing distance of Gracie, pulled her close and whispered something in her ear.

“No,” the child insisted with an adamant shake of her head. “I don’t need to.”

“I think you do.”

Crossing one leg over the other, Gracie said, “I just need another piece of chalk so I can finish.”

“First the W.C.,” Nell said as she reached for the child. “Then I’ll fetch you some more chalk.”

“I’ll take her,” said Viola as she crossed the room, wheels rattling over the slate. “You’d best finish sizing that canvas before the glue dries up. Come along, Gracie.”

“But I don’t–“

“We’ll stop at the kitchen afterward and have Mrs. Waters make you a nice cup of hot cocoa.”

Gracie dropped the chalk and hurried after her nana. “Can I wide on your lap?” she asked as she followed Viola into the hall. “Can I? Please?”

“Can you?” Viola challenged.

“May I?” she implored, while dancing that little telltale dance. “Please, Nana?”

“Er…perhaps on the way back.”

Will smiled as he watched them retreat down the hall. There was amusement in his eyes, and pride, and a hint of wonderment at the child he’d created quite by chance one lonely night with a pretty young chambermaid during his last visit to his family.

It had been a Christmas furlough from his service as a Union Army battle surgeon in December of 1863, shortly before he was captured and imprisoned at Andersonville, along with his brother Robbie. After the hellish prison camp claimed Robbie’s life, Will escaped and, wounded inside and out, and allowed his family to think was dead for years while he lost himself in a numbing haze of opium smoke and cards.

“What the devil is that stuff, anyway?” Will asked as Nell dipped up another spatula full of warm, gelatinous glue.

“Rabbit skin glue. Canvases have to be sized with this and then primed with gesso before one can paint on them.”

“She makes you prepare her canvases? And on a Saturday? I thought you had Saturdays off.”

“I do,” Nell said as she smeared and scraped. “This is my canvas, for a painting I’m planning of Martin and some of his divinity school friends rowing on the Charles River.”

“Which ones are yours?” he asked, scanning the solarium-turned-studio. The only painting he’d ever seen of hers was the portrait of Gracie that she gave him for his birthday in July, which hung over the fireplace in the little library of his Acorn Street house. It captured Gracie’s winsome charm, which was why she’d wanted Will to have it, but it was sketchier than her usual work, because she’d been trying to suggest movement as the child played with her dolls.

Nell guided him around the room, pointing out paintings on easels, leaning against walls, and stored in drying racks–portraits and street scenes, mostly, a few interiors.

“Nell, I’m…awestruck,” he said after he’d viewed them all. “Your handling of light is incredible. These paintings–they glow from within. Why have you never shown me these before?”

“You’ve never been to the house before–not since I’ve lived here.” Nell turned back to the canvas she was sizing as her face suffused with heat.

“Are you blushing?” There was amusement in his voice as he came up behind her. He liked to make her redden, then tease her about it, and it wasn’t hard, with her coloring. Although she wasn’t quite a redhead, her hair being a sort of rust-stained brown, she was cursed with the volatile complexion of that breed–pale, translucent skin that sizzled at the drop of an innuendo.

“You are, aren’t you?” he asked.

“No.” There was something about blushing with pride from Will’s praise that made her feel particularly exposed, as if that which lay in the deepest recesses of her heart were emblazoned in scarlet all over her face for the entire world to see.

“I think you are.” He was standing so close that his legs rustled the silk faille skirt beneath her smock frock. “What the devil…?”

Her scalp tickled as he slid one of the filbert brushes out of the twist of hair at her nape, loosening it. “Ah, the ever practical Miseeney,” he chuckled.

“You’re making it come undone,” Nell said over her shoulder, the movement causing the chignon to unfurl heavily down her back. She bent to retrieve the second brush as it clattered onto the slate.

“I’ve got it,” Will said as he stooped to pick it up, bracing a hand on his bad leg.

Nell glanced back over her shoulder, reaching for the brushes.

“Allow me.” Slipping the brushes into his coat pocket, he shook out the rope of hair and slowly combed his fingers through it, sending little shivers of pleasure into her scalp.

“You know how to put a lady’s hair up?” she asked, heavy-lidded from the gentle pulling and tugging.

“I know quite a few things I probably shouldn’t.”