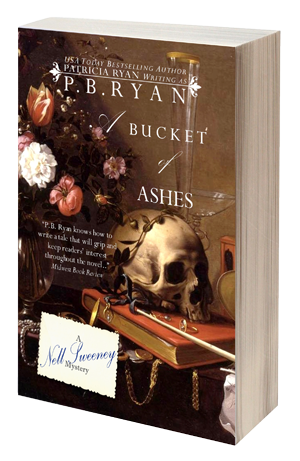

Excerpt: A Bucket of Ashes

Book 6: Nell Sweeney Mysteries

August 1870: Cape Cod, Massachusetts

“Miseeny, who’s that man?” asked breathless little Gracie Hewitt as she treaded water in Waquoit Bay flanked by the two young women charged with her care.

“What man, buttercup?” Nell Sweeney, standing waist-deep in the placid water, followed Gracie’s gaze toward the Hewitts’ colossal, cedar-shingled summer “cottage.” Shielding her eyes against the late afternoon sun, she saw a man walking toward them across the vast stretch of lawn that separated the shore from the house. Lean and with a graceful gait, he wore a well-tailored cutaway sack coat and bowler. It wasn’t until he removed the bowler and smiled at Nell–that warm, genial smile she’d once known so well–that she recognized him.

“Oh, my word,” Nell murmured.

“Who is he, then?” asked Eileen Tierney in her softly girlish brogue.

“He’s, um, someone I used to know when I lived here on the Cape. I haven’t seen him for some time.”

It had been three years since Nell, who lived in Boston with the Hewitts except for summers here at Falconwood, had last crossed paths with Dr. Cyril Greaves. In July of ‘sixty-seven, she had accompanied her employer, Viola Hewitt, to a charity tea in Falmouth, and he’d been there. Their conversation had been cordial–affectionate, even–but as if by unspoken agreement, neither had made any move to resume their acquaintance. Two summers before that, they’d passed each other on Short Street in Falmouth, he in his all-weather physician’s coupe and Nell in her little Boston chaise, and had chatted for a minute until a salt wagon rumbling up behind Dr. Greaves had forced him to move on.

For him to actually seek her out this way was unusual enough to be disconcerting.

“Och, but he’s a handsome fella,” whispered Eileen.

“He’s married,” Nell said. “And he’s older than he seems.”

The first time Nell had seen Dr. Greaves, she was struck by his resemblance to a statue of St. Francis of Assisi in front of St. Catherine’s, her parish church. Born with patrician good looks, expressive eyes, and that ready smile, he was further blessed by being one of those lucky men who didn’t seem to age much in their middle years. His light brown hair had but a whisper of gray at the temples, and he still moved like a man in his twenties.

“Is he nice?” Gracie panted, switching to a dog paddle to keep up with Nell as she waded toward shore.

“He is very nice.”

“Can I meet him?”

“Can you?”

“May I?” asked the child with a put-upon roll of the eyes.

“You have met him. You just don’t remember.”

“I’d like to meet him again.”

Nell paused at the edge of the bay to wring out the sodden, knee-length skirt of her bathing costume as Dr. Greaves crossed the sandy stretch of beach. She looked up to find him taking in her attire–the puffy cap, black wool sailor dress, matching pantaloons, and lace-up slippers–with a contemplative smile that made her cheeks bloom with heat.

“Oh, do stop gaping at me,” she said through a flutter of embarrassed laughter.

“Is that any way to greet an old friend?”

Old friend. Curious, Nell thought, that Dr. Greaves should refer to himself that way. Much as they’d cared for each other, they’d never been friends, precisely; certainly she’d never thought of them as such.

“And I wasn’t gaping,” he said. “I was admiring.” Before Nell could summon a reply to that, he turned to greet Gracie and Eileen with a bow. “Ladies. So sorry to intrude upon you unannounced like this, but the butler told me you were out here, and that I should just come on back.”

“Quite right,” Nell said. “Grace Hewitt, Eileen Tierney, may I present Dr. Cyril Greaves, a physician from East Falmouth.” To Dr. Greaves, she said, “Miss Tierney helps me to look after Gracie, with whom you are already acquainted.”

“I’m most pleased to see you again, Miss Hewitt,” said Dr. Greaves.

“And I you,” said Gracie, the consummate little Brahmin lady in her short white bathing dress and damp braids.

The child’s decorous reply drew an impressed grin from Dr. Greaves. “I must say, that is a much more mannerly salutation than the red-faced squalls with which you greeted me the first time we met.”

“Dr. Greaves is the physician who took you out of your mommy’s tummy,” Nell told Gracie.

“With Miss Sweeney’s help,” he said. “I couldn’t have done it without her.” A gracious statement, indeed, for it was he and he alone who had saved both Gracie’s life and that of her mother, a chambermaid named Annie McIntyre, by means of a deft and timely Cesarean section that storm-ravaged night six years ago. Meeting Nell’s gaze, he said, “I should never have let her go.”

Looking up at Nell, eyes wide, Gracie said, “You were there when I was born?”

She hesitated. Dr. Greaves winced, evidently realizing he’d just revealed something that Nell, in an effort to forestall Gracie’s incessant questions about her parentage, had kept to herself. With the cat out of the bag, Nell nodded and said, “I was Dr. Greaves’s assistant for four years. Then, after you arrived and Nana decided to adopt you, she asked me if I would come to Boston to be your nursery governess.”

But not before questioning Dr. Greaves, in a conversation overheard by Nell, as to her suitability to care for and tutor a young girl. She’s of good character and chaste habits, I take it?His response had been reassuring, if purposefully vague. There’d been no hint–thank God, because Nell had desperately wanted the position–of her disreputable past, nor of the fact that she’d been sharing the lonely doctor’s bed for three of the four years in which she’d lived under his roof.

From a good family, is she? Mrs. Hewitt had asked him.

They were from the old country, ma’am. Both gone now, first him and then the mother, when Nell was just a child.

And there’s no other family?

She had a number of younger siblings–that’s how she learned to care for children. Disease took most of them–cholera, diphtheria–but one brother lived to adulthood. She assumes he’s still alive, but it’s been years since she’s seen him. James–she calls him Jamie.

Nell had let out the breath she’d been holding, weak with relief and gratitude that he hadn’t mentioned Duncan. The rest of it was damning enough, but if Viola had known about Duncan, there would have been no question of hiring her.

Naturally, Viola had told Nell when she offered her the position, I would prefer that you remain unwed while Grace is young, in order to devote your full attention to her. And, of course, your conduct and reputation must be above reproach–you’re responsible for the upbringing of a young girl, after all. But I can’t think you’d let me down in that regard.

If Nell had managed, these past six years, to live up to Viola’s expectations, it was only by perpetuating a lie of omission to a woman she’d come to regard as a surrogate mother. As far as Viola knew–then and now–Miss Nell Sweeney was a virtuous Irish Catholic girl from a working class background who was good with children. There’d been so much Nell had been obliged to keep hidden all these years, lest she risk the loss of her position, her wonderful new life, and most unthinkable of all, Gracie.

“Miseeny?” Gracie was tugging at her skirt. “Did you?”

“Did I what, sweetie?”

“Know my mommy? My weal mommy? Real,” she added, correcting herself before Nell could.

“I had never met her before that night,” Nell answered truthfully.

“Did you?” she asked Dr. Greaves.

He shook his head. “I’m sorry, no.”

Nell said, “Gracie, you know what Nana says. She’ll tell you about your mommy as a birthday present when you turn twelve.”

Although the child was equally curious about her father, there had been, at his insistence, no such promise to reveal his identity. Recently Gracie had overheard Mrs. Mott, the housekeeper, say that she’d been “sired by a Hewitt,” and had pressed Nell as to what that meant. In response, Nell had uttered the only outright lie she’d ever told the child: “‘Sired’ means adopted. Mrs. Mott was talking about Nana’s having picked you out special because she’d always wanted a little girl.”

Eileen, adept at changing the subject when it veered down this particular path, said to Dr. Greaves, “You’d be the one, then, that taught Miss Sweeney nursing.”

“More than just nursing,” Nell said. “He taught me arithmetic, French, history, music, comportment… I didn’t even know how to write a proper letter till Dr. Greaves got hold of me.” He’d been her Pygmalion, she his grateful Galatea.

“Nell had an extraordinarily quick mind,” Dr. Greaves told Eileen. Eyeing the delicate, flaxen-haired nineteen-year-old with keen interest, he said, “Forgive me, Miss Tierney, but have we met?”

“I don’t figger we could of, sir. I only been in this country two years, and I never set foot on the Cape till this summer.”

“You look familiar, but perhaps I’m just confusing you with someone else.” Dr. Greaves turned to Nell. “I, er, wonder if I might have a word with you.” He glanced at Gracie and Eileen. “Perhaps we could take a walk?”

“You go ahead, Miss Sweeney,” said Eileen. “I’ll take Gracie back to the house and get her washed up and fed.”

Nell and Dr. Greaves strolled in silence along the beach toward a handsome edifice adjacent the Hewitts’ private dock, built half on land and half on stone pilings in the water. Like the estate’s main house, it was cedar-shingled, with slate-roofed gables, a turret, and a veranda overlooking the bay, from which stairs descended to the dock. The ground level, which was open to the bay and fitted out with two boat slips, housed a small sailboat, a rowboat, a canoe, and a pair of sleek shells. Above that was a guest suite.

“So that’s the famous Falconwood boathouse, eh?” asked Dr. Greaves as they neared it. They say it’s the grandest on the Cape. Mr. Hewitt sails, I take it?”

“Not anymore,” said Nell, knowing that Dr. Greaves hadn’t come here to talk about the boathouse, and wondering why he was stalling; he wasn’t the type of man to beat about the bush. “Martin, the youngest son, takes one of the shells out a couple of times a day when he’s here, as long as the weather’s amenable. He’s out there right now.”

“Martin, he was the pious one, yes?”

Nell nodded. “He’s a minister at King’s Chapel now. His first sermon was right before I left Boston, and it was brilliant. I can’t remember when I’ve been so moved.”

“A devout Catholic like you, attending a Unitarian service? That must be good for an extra few eons in purgatory.”

“Actually… I’ve been attending services at King’s Chapel for some time now.”

Dr. Greaves stopped in his tracks at the side of the house where the dock began. “You’re joking.”

“Now you really are gaping at me.”

“You? A Protestant?”

“It’s a long story.”

Dr. Greaves gestured toward the sixty foot dock, which terminated in a large raised platform set up with lounging furniture, and offered his arm. “Shall we?” As he escorted her down the narrow plank walkway, he said, “The other son was more of a rogue, as I recall. Squirmed out of joining the Army during the war… Henry?”

“Yes, but they call him Harry, and ‘rogue’ is a very polite term for what he is. He’s not the only other Hewitt son, though. There’s the eldest, William.”

“But I thought William died at Andersonville, during the war, he and the next eldest, Robert. I’m sure that’s what we were told that night we delivered Gracie.”

“Robbie died. Will escaped, but it took him years to reunite with his family.” Not that he was ever ‘reunited,’ precisely, with the rigid and judgmental August Hewitt, who couldn’t bear the sight of him–or of Nell, for that matter.

“William–he was the one who earned his medical degree at Edinburgh?”

“Yes, he was brought up with relatives in England, but he came back here when war was declared and enlisted in the Union Army as a battle surgeon.”

“Did he establish a practice after the war?”

Nell chose her words carefully, lest Dr. Greaves conclude, as had August Hewitt, that Will was a reprobate of the first order. “He hasn’t practiced medicine since then–although he treated Eileen for her clubfoot last year.”

“Your assistant? She doesn’t have a clubfoot.”

“Not anymore. Will arranged for a famous orthopedic surgeon from New York to come to Boston and operate on her.”

Dr. Greaves snapped his fingers. “That’s where I know her from. Louis Albert Sayre was the surgeon–brilliant man. I watched that operation in the surgical theater at Massachusetts General.”

Nell was going to say something about his professional dedication in coming all the way up to Boston from the Cape when she recalled that he made that trip every week or two to visit his beloved wife, Charlotte, who’d been a psychiatric patient at Mass General since well before the war.

“Eileen does wear special, custom-made boots,” Nell said, “but she hardly limps anymore. Will was very pleased with the outcome.”

“If he hasn’t been practicing medicine since the war,” Dr. Greaves asked, “what has he been doing?”

Gambling and weaning himself off opiates. “He taught medical jurisprudence at Harvard one semester,” she said. “His closest friend, Isaac Foster, is assistant dean of the medical school, and he’s issued Will a standing offer of a full professorship so that he can develop a forensics curriculum, but there’s a catch. Will would have to sign a five-year contract, and he’s… not comfortable with that kind of commitment.”

“Not comfortable with a full professorship at Harvard Medical School?” Dr. Greaves asked incredulously.

Stepping up onto the platform, Nell turned to look out over the water, her arms wrapped around herself. “Will is a… complicated man. And, too, he’d had another offer. President Grant wrote him recently, when France and Prussia started mobilizing for war. Our ambassador to France, Elihu Washburne, was asking for a good field surgeon. The president had met Will several times during the war, and he came away with a very high opinion of him.”

“A field surgeon? But we’re not allied with France in that war. We’re entirely neutral.”

“Mr. Washburne isn’t, and he’s resolved to remain in Paris and do what he can to aid France, never mind that it’s utter bedlam there now. Will accepted the position.”

“Why would any American in his right mind risk life and limb in a fight that isn’t ours, that isn’t even particularly righteous? It’s just so much chest-beating between Napoleon and Wilhelm.”

“He had his reasons,” said Nell, thinking of the letter Will had left on her pillow the night before he took ship, three and a half weeks ago. You will wonder why I’ve chosen this course, rather than the more comfortable alternative of teaching at Harvard. We have reached a juncture in the path of our acquaintance, you and I, from whence we cannot continue as before, strolling along side by side with no particular destination in mind, at least none of which we dare speak….

“Is he to remain in Paris,” asked Dr. Greaves, “or provide medical service in the field?”

“The latter. Last week he cabled me from Paris to say that he would be leaving the next day to serve Napoleon’s army.” Am to join Marshal MacMahon’s I Corps near Wissembourg on German border and remain with them for duration of war. Unable to write for some time, perhaps months. Please do not worry, and ask same of Mother and Martin.

“He cabled you?”

“We’ve… become friendly over the past couple of years.”

Dr. Greaves was studying her in that all too insightful way of his. “When is he to return?”

“Not until the war ends. He told me it could be months from now, or–” Her throat closed up around the word “years.”

“Ah.”

“What was it that you wanted to talk to me about, Dr. Greaves?”

He nodded toward a pair of wicker rocking chairs. “Let’s sit.”

She lowered herself into the chair he held steady for her, and then he turned the other chair to face hers. He sat forward with his elbows on his knees and expelled a lingering sigh. “A young woman was brought to me this morning for medical treatment. A girl, really–nineteen, but a young nineteen. Claire Gilmartin is her name. She lives with her widowed mother on the outskirts of East Falmouth. They have a little cranberry farm on Mill Pond. You remember Mill Pond, just to the west of the village?”

“Of course,” said Nell, rocking absently.

“Claire had grown hoarse and developed a wheezing cough that morning, with dark sputum. She seemed a bit mentally confused as well, but that may have just been her way. There was no mystery as to the cause of her malady. One of their outbuildings–they called it a cranberry shed–had burned down the night before last, and Claire had been trapped in it for a little while before she managed to escape.”

“This happened, what–thirty-six hours before, and she’d only just started coughing this morning?”

“The symptoms of smoke inhalation can take that long to develop. In any event, it appears that a man unknown to them had gotten caught in the fire and died. Yesterday, when the ashes and debris were cleared away, his remains were removed and taken to Falmouth for assessment by the county coroner. According to Mrs. Gilmartin, he was one of those two men the police have been looking for, the ones who shot that woman in the beach house.”

“I’m sorry,” Nell said. “I don’t have any idea what you’re talking about. We’re really rather isolated here.”

“You don’t read the Barnstable Patriot, I see. Do you get the Boston papers, or do without altogether when you’re summering here?”

“Mr. Hewitt brings the Boston papers when he comes down for the weekends, but we get the New York Herald every day, and that’s what I’ve been reading. It comes on the train from New York. Brady, the Hewitts’ driver, goes to Falmouth and gets it.”

“Every day? That’s almost an hour’s drive each way.”

“It’s because of the war, and Will being over there. Mrs. Hewitt wants to keep apprised of all the new developments–as do I, of course.”

“Understandable–as is your lack of interest in local doings, I suppose, given that you’re only here for summer relaxation. But to those of us who live here year-round, the Cunningham incident was big news. It happened a couple of weeks ago. Susannah Cunningham was shot dead by burglars in her home–one of those huge new summer palaces in Falmouth Heights.”

“How awful.”

“The burglars got away, albeit empty-handed, and the Falmouth constabulary has spent the past two weeks searching for them. There’d been some evidence that they were still in the area, in hiding.”

“One of them in the Gilmartins’ barn,” Nell said.

Dr. Greaves nodded. “The body was identified last night. Mrs. Gilmartin told me his name and said it would be in the Patriot today. It comes out on Thursdays normally, but they’re issuing an extra. I didn’t want you to read about it without being prepared.” Dr. Greaves gentled his voice, his expression bleak. “I hate to have to tell you this. She said his name was James Murphy.”

Nell stopped rocking. She stared at Dr. Greaves.

“I’m so sorry, Nell.” He reached over to squeeze her hand.

“How… how do they know it was him if he’d… if he’d been burned? Wouldn’t he have been…?”

“I don’t know. I only know what Mrs. Gilmartin told me.”

“Are you sure it was Jamie?” She asked. “Murphy is such a common name. So is James.”

“I suppose,” he said, but she could tell he was humoring her. “Have you been in touch with your brother at all these past…?”

“No, not since he was sent to prison for robbing that livery driver in ‘fifty-nine. The first time I came to visit him, he told me not to come again, that he didn’t want any visitors, even me. I did come again, but he wouldn’t see me. I wrote to him after Duncan was arrested, to let him know what had happened, and that I was living at your house, but he never wrote back. Of course, he wasn’t much for writing, but I think he could have managed a short note–something.”

“How long was his sentence, again?”

“Eighteen months. I thought perhaps he would look me up after he was released, but he didn’t. I began to worry that perhaps he’d been killed by another prisoner, or caught some disease in there, so I wrote to the superintendent of the Plymouth House of Corrections–remember? You helped me to compose the letter.”

“Oh yes, I remember.”

“He wrote back saying that Jamie had been released in May of ‘sixty-one. I never heard from him again. He was fed up with me and my preaching about how he should live his life. Who could blame him, especially considering how I was living mine at the time. A classic case of the pot calling the kettle black.” Nell had often wondered, this past decade, what had become of the ne’er-do-well younger brother who was her last remaining sibling, the rest having succumbed before they’d made it to adolescence. Jamie’s most likely fate, she’d supposed, would have been another prison term. She’d thought that was the worst it would come to.

“Nell?”

Nell realized she’d been staring dully at the opposite shore. She should be crying, she should be consumed with grief, but she had the most curious sensation of being wrapped in cotton wool. The brick wall of respectability she’d built around herself since moving to Boston had served to insulate her from a past tainted by poverty and pestilence and vice, a past of which Jamie had been an integral part. In the interest of self-preservation, she’d cultivated an emotional distance from everything she’d been and done during the first eighteen years of her life, everyone she’d known–even her own brother. Now, it was as if someone were taking a sledgehammer to that protective wall, trying to bash a hole in it.

Gripping the arms of her chair, she went to rise from it, forgetting that it was a rocking chair. It swayed, and she with it, the blood draining from her head so fast that she nearly keeled over. No doubt she would have, had Dr. Greaves not caught her up and eased her back down onto the chair.

“Relax,” he said, pressing gently on her head to lower it. “That’s right. Take deep breaths.”

“I’m all right,” she said, feeling starved for air. “I just… it’s just this blasted heat.”

“And this awful news, I should imagine.”

“Yes, of course,” she said.

“We’ll stay here till you’ve got your bearings,” he said, “and then I’ll walk you back to the house.”

***

“Do you remember the first time you saw this house, that night we came here to deliver Gracie?” asked Dr. Greaves as he escorted Nell by the arm onto the back porch, one of four ringing the palatial house. She knew that the purpose of his patter, which he’d kept up during the walk from the beach to the house, was to keep her mind off Jamie. It was the same trick he used, and had taught her to use, to keep patients calm. “You called it a castle. You couldn’t believe the Hewitts only spent six weeks a year here.”

“You told me it had over twenty rooms,” said Nell, trying to shake off the numb shock that gripped her. “There are actually forty, if you count the servants’ rooms and nurseries on the third floor.”

“Nell?” came a woman’s British inflected voice. “Is that you?”

They entered the vast and opulent great hall to find Viola Hewitt sitting in her wheelchair, silhouetted by the sunlight streaming in through the two-story bay window on the back wall.

“Mrs. Hewitt,” Nell said, “do you remember Dr. Greaves?”

“How could I forget?” Viola wheeled toward them, guiding the chair around a pair of leather-upholstered settees flanking the monumental fireplace. Between them was a sheepskin rug on which Gracie’s little red poodle, Clancy, lay curled up asleep. “Our Gracie might not have survived that night without you. How very lovely to see you again, Dr. Greaves,” she said as she extended her hand.

“The pleasure is all mine. I must say, Mrs. Hewitt, you’ve changed very little these past six years. You are quite as handsome a lady now as you were then.”

Idle flattery it may have been, but it was also the simple truth. The tall, angular Viola Hewitt, with her silver-threaded black hair and serene eyes, was the most striking woman Nell had ever met. Of her four sons, the only one who assembled her was Will. Martin, Harry, and the late Robbie were fair, like their father.

Viola was dressed this afternoon in one of the flowing, silken tea gowns she favored for daytime wear, her throat and circled by a hefty turquoise necklace from Mexico that few other Brahmin matrons would deign to wear. On her lap was the silver mail tray from the hallstand by the front door, which held an envelope and an unfolded letter.

Will you stay for supper, Dr. Greaves?” Viola asked.

“I wish I could, but I have some patients to visit this afternoon, so I must to be on my way.”

“You must join us Friday, then. I’m giving a little dinner to celebrate the return of my son Harry and his new bride from Europe. They’re in Boston now, but they’ve decided to spend a few days here with us. Mr. Hewitt will be coming down with them on the train for the weekend, and my son Martin will still be here. He doesn’t have to return to Boston until Saturday.”

“What a kind invitation, Mrs. Hewitt, ” he said. “I believe I would enjoy that, especially if Nell can join us.”

“Why not? Eileen can feed Gracie her supper that night. And please call me Viola. I’m really not very keen on formality.”

“Then you must call me Cyril.” Turning to Nell with a smile, he said, “Both of you.”

Nell wasn’t quite sure how to respond to the implied shift in their acquaintanceship. “I don’t know if I could get used to that. Old habits, you know.”

“Do try,” he said. “It would please me.”

Nell walked him through the entry hall and onto the front porch, whereupon he touched her arm, saying quietly, “Are you going to be all right?”

“It’s doesn’t seem real. Maybe it isn’t. Maybe it wasn’t even Jamie. If only there were some way to find out for sure.”

“I would imagine it was the police who identified him,” he said. “If you’d like, I can take you to see the Falmouth chief constable tomorrow. He’s got jurisdiction over East Falmouth. You can ask him how he made the identification–if Gracie can spare you for a few hours.”

“Eileen can look after Gracie. I would like to talk to the constable. It’s very kind of you to offer, Dr. Gr–Cyril.”

He smiled. “See? That wasn’t so hard, was it?”

He told her he would come by for her at ten the next morning, and took his leave.

“I know it may be none of my affair,” said Viola as Nell rejoined her, “but it’s clear you’re troubled. Is it anything you’d care to talk about?”

“It’s… about my brother Jamie,” Nell said. “Or someone with the same name, but… that’s probably wishful thinking.”

Viola looked a little surprised that Nell had brought up the subject of her brother, as well she might. Nell never spoke about Jamie, nor had she ever corrected Viola’s assumption that they’d had a falling out years before. How else to explain an estrangement of eleven years that was due not so much to ill feelings as to Jamie’s disinclination to have anything to do with her? And what was Nell supposed a to answer, should Viola ask her what her brother did for a living? He’s been a petty criminal since he was a child, mostly sneak thievery, robbing drunks, and holding up carriages on out-of-the-way roads. And picking pockets, which, as a matter of fact, happened to be a particular talent of mine.

“Has your brother been in contact?” Viola asked.

Nell shook her head, looking down. “He… Dr. Greaves thinks he’s been killed. In a fire.”

“Oh, my dear.” Viola wheeled closer and grabbed Nell’s hand. “Oh, what dreadful news. I am so terribly, terribly sorry.”

“I… I still don’t quite believe it. I don’t think I will until I speak to this constable tomorrow.”

Folding up the letter in her hand, Viola said, “This can wait, then.”

“What is it?” Nell asked.

“It’s nothing. It’s not important, not now, while you have so much on your mind.”

Nell’s gaze lit on the envelope lying faceup on the silver tray. Reading it upside down, she saw that it was addressed to Mr. and Mrs. August Hewitt in a strained, almost juvenile hand. Her mouth flew open which he saw the name on the return address: Chas. A. Skinner.

“That’s from Detective Skinner? Why on earth would he write to you?” asked Nell. “He barely knows you.”

“It’s not ‘Detective’ anymore, remember? It’s not even ‘Constable.'”

“Of course. It’s just force of habit to call him that. Loathsome little weasel.”

Charlie Skinner, once a member of the elite but defunct Boston Detectives Bureau, had been downgraded at the beginning of this year to uniformed patrolman on the weight of his corruption and myriad misdeeds. Unwilling to accept that this demotion was his own doing–his type never was–he blamed Nell’s friend, State Detective Colin Cook. So virulent was his hatred of the Irish detective that he plotted to get Cook convicted of a murder he hadn’t committed. The scheme turned against him, though, thanks in large part to Nell and Will, and last month he was booted off the force altogether.

“What did he write to you?” Nell asked.

Choosing her words with evident care, Viola said, “Mr. Skinner obviously harbors a great deal of anger toward you for being the instrument of his downfall. It’s nothing you need trouble yourself over during this difficult–“

“Mrs. Hewitt,” Nell said quietly. “Viola. Please.”

Viola looked from Nell to the letter, grim-faced. “Have a seat, my dear,” she said, nodding toward the nearest settee.

“My bathing dress is wet. I don’t want to get–“

“Sit, Nell.”

Nell sat, shivering in her damp swimming clothes. Viola unfolded the letter and handed it to her.

Boston Friday, July 29, 1870

My Dear Sir and Madame,

You will no doubt wonder why I who am barely aquainted with you have penned this missive. By way of explanation may I explain that until recentley, which is to say the 9th of July, I was employed by the City of Boston as a Constable, a fact which is known to Mrs. Hewitt who may regard me ill but who I pray will credit the contents of this missive. In the days preceeding my termination I was engaged in inquiries pursuant to my Constabulary duties, which inquiries were thwarted hammer and tongs by the ill-advised labors of the Irish female who you employ as a governess, in concequence of which I was as I say relieved of my duties.

As I am led to understand that you hold the highest regard for Miss Sweeney, who is no “miss” as I shall explain–

Looking up sharply, Nell saw Viola sitting in front of the bay window with her back to the room, gazing out onto the exquisitely landscaped north lawn and the bay to the east. Nell returned her attention to the letter, her hands shaking so badly that she could barely focus on the words.

As I am led to understand that you hold the highest regard for Miss Sweeney, who is no “miss” as I shall explain, it falls to me as a man of rectitude who is vexed to see good folks such as yourselves gulled by a cunning Colleen to inform you that “Miss” Sweeney is in no way what she appears to be. On the 8th of July in the course of my afore-mentioned duties I had ocassion to observe “Miss” Sweeney leave your home on Tremont St. and hire a hackney coach, her uneasy manner arousing my intrest to the degree that I followed her at a distance in my gig North across the river to Charlestown.

The hack proceeded to Charlestown State Prison, the driver waiting outside the gate as “Miss” Sweeney entered the Prison where she remained from one o’clock in the afternoon until half passed that hour. When she came out and got back in the hack I could not help but notice that her color was high and her atire unkempt withal. Which is to say her hat being crooked and a fair degree of dust besmirching the back of her dress.

You can imagine my cogitations as to what such a visit might betoken. Upon finding myself two days thence in posession of considerable free time I set about making inquiries as to the nature of that visit. Such inquiries being hindered by my being sacked and the stain upon my repute it took me some time to sort things out. But at length I became privy to the truth, which is that “Miss” Sweeney is MRS. Sweeney wife of Duncan Sweeney inmate at Charlestown State Prison these 10 years passed with 20 more years to serve for the crimes of armed robbery and aggravated assault.

Knowing that good folks such as yourselves could not and would not countenance such bald DECIET I took pen to paper so that you might know how you have been hoodwinked and act accordingly, which is to say sack MRS. Sweeney with all haste. I warrant she is as Bad an Apple as ever washed up on our shores.

Ever most faithfully yours,

Chas. A. Skinner

Nell lowered the letter, sweat beading coldly on her face. Please, St. Dismas. Please don’t let this happen. I can’t lose her. I can’t lose Gracie.

She pressed a hand to her stomach as it pitched, launching a surge of bile into her throat. “Oh, God.”

Bolting up from the settee, she raced through the buttery and down the service hallway to the little bathroom off the laundry room, hunched over the water closet, and emptied her stomach. She flushed, rinsed out her mouth, and surveyed herself in the toilet glass. Her face was waxen, her eyes panicky. She whipped the absurd bathing cap off her head, and with palsied hands smoothed down her hair, plaited into a single, still damp, rusty brown braid.

“God, help me,” she whispered, and walked back to the great hall on legs that felt as if they were made of India rubber.

Viola was sitting with the letter in her hand, watching Nell gravely; Clancy, sitting next to her, bore a similar expression. “Are you quite all right?”

Nell nodded, although, of course, she was anything but. “It’s the heat,” she said dully as she wiped her forehead with the back of her arm. “This blasted heat.”

“And this letter, I should think. From your reaction… It’s true, I take it.”

Nell sank to her knees in front of Viola, her strength utterly sapped by the double volley of bad news in such a brief period of time. “I’m sorry, Mrs. Hewitt,” she said in a watery voice. “I’m sorry. I… I never meant to deceive you. That is, I never wanted to. I hated it, I always hated it. But I just… I knew I couldn’t be Gracie’s governess if I was married, especially to a… to someone like Duncan.”

“Does Will know?” Viola asked. All she knew about Nell and Will was that they’d developed a friendship based on common interests, not the least of which was Gracie. When people had started whispering about the amount of time they were spending together, they pretended to be engaged in order to protect Nell’s reputation. Viola knew about the bogus engagement, as did her husband.

“He knows,” Nell said. “And Dr. Greaves. And, of course, Father Gannon at St. Stephen’s. And Father Donnelly at St. Catherine’s in East Falmouth. He was my confessor before I moved to Boston. No one other than them.”

Viola sat back in her chair, nodding pensively, her gaze on the letter.

“Mrs. Hewitt…” Nell said, swallowing down the urge to burst into tears. Viola, with her classic British restraint, disdained emotional outbursts. “Gracie means everything to me. I couldn’t give her up. I’d rather die.”

Viola stared at Nell, and then her expression softened, and she said, “Oh, Nell. Oh, my dear.” Leaning down, she stroked Nell’s cheek with her cool, soft hand. “You think I’m going to dismiss you? How poorly you know me.”

“But… Mr. Hewitt, when he reads that letter…”

Through a little gust of laughter, Viola said, “Mr. Hewitt is never going to read this letter.”

She spun her chair around, plucked a match safe off a console table, and wheeled over to the fireplace. Scraping aside the summer screen of stained glass, she tossed the letter and envelope onto the empty grate, lit a match, and threw it in. Within about two minutes, all that was left of Charlie Skinner’s damning “missive” were some flakes of black, papery ash.

“Here, let me get that,” Nell said as Viola went to replace the heavy screen. Pulling it back over the hearth, she said, “I… I don’t know how to thank you, Mrs. Hewitt. I am sorry for having misled you, dreadfully sorry.”

“Well, I mean, obviously I would have preferred that you’d been candid with me, but looking back, it wasn’t really outright deception. I assumed from the beginning that you were unwed. You simply never corrected me.”

“You’re being generous, Mrs. Hewitt. I did call myself Miss Sweeney. I’d stopped calling myself ‘Mrs.’ ever since Duncan… well, ever since he went to prison. I’ve worried for six years about what would happen if it became known that I was married to a convict. I’m truly humbled by your kindness and your understanding.”

“Do sit down, my dear. You’re so very pale.”

Mindful of her damp clothes, Nell sat on the edge of the hearth.

“I ought to be understanding,” Viola said. “I’ve a skeleton rattling ’round in my own closet, after all.”

Nell was one of two people, Mr. Hewitt being the other, who knew that at the time of the Hewitts’ wedding, Viola was some five months pregnant by the French painter Emil Touchette. During a calculatedly lengthy European honeymoon, Viola gave birth to Will, whom August had never been able to accept as his own, despite his well-meaning assurances to that effect when he proposed to Viola.

“But to be quite frank,” Viola continued, “had I known about Duncan six years ago, I can’t say it wouldn’t have given me pause, not just because your husband was in prison, but because you had a husband. I was concerned about your attention being divided while Gracie was young. As it turned out,” she said with a wry smile, “your husband’s imprisonment ensured that you were able to devote yourself fully to Gracie.”

“I love her as if she were my own. For the longest time, I thought I’d never…” Careful. Viola was tolerant and indulgent, remarkably so, but there would be a limit to how much even she could accept. “I thought I’d never have a child to love and care for, but now I have Gracie, as she means the world to me.”

“You needn’t discuss this if you don’t want to,” Viola said. “It’s really none of my affair, after all, but I can’t help but wonder why a fine young woman such as yourself would, well…”

“Get involved with the criminal?” With a cheerless smile, Nell said, “Don’t think I haven’t asked myself that same question many times. The thing is, I didn’t realize what he was when I first met him. My… my brother Jamie introduced us. He brought Duncan around to the poor house to meet me, and–“

“Poor house?” said Viola, obviously aghast.

Nell lowered her gaze to her hands, twisting the hem of her bathing dress as if to wring it out. “The Barnstable County Poor House. I hadn’t wanted you to know. I felt… well, I was ashamed, of course, but I was also worried that if you knew how I’d grown up, you’d consider me unsuitable to be a governess.”

“I don’t judge people by their backgrounds, but by who they are–though I must say, you’re having turned out so well after enduring such an upbringing speaks well for your character. Did you live there for your entire childhood?”

Nell shook her head. “Only from the age of eleven. Before that, I lived in East Falmouth. My father was a day laborer on the docks, when he was working. But he was a drunk, and he abandoned us. A year later my mother died of cholera, along with one of my sisters and two of my brothers.”

“Oh, Nell.”

“Another sister had died three years before–some lung ailment, I’m not really sure what it was. So that left Jamie and Tess and me. Jamie was a year and a half younger than I, and Tess was just an infant, a newborn. We were sent to the poor house, which was…” Nell shook her head, her eyes closed. “You can’t imagine.”

“I’ve done charity work in those places, remember? I can imagine all too well.”

“At least I had Tess to take care of, and that gave me the sense that God had a plan for me, that I wasn’t just a charity case, that I was doing something worthwhile. She was the sweetest little thing, Tess, with big, dark eyes, just like Gracie. But, um…” Nell took a deep, shaky breath. “She died of diphtheria when she was just shy of her fourth birthday.”

Viola closed her eyes with a pained expression.

Nell looked away from her so as to stifle her urge to weep. “Jamie ran off then, said he had enough of being a ward of the state, and that he was going to make his own way from now on, never mind he was just twelve. I was tempted to leave, too, but a girl my age on her own… I’d seen enough unwed mothers come and go through those doors to know how it would have turned out.”

“A wise decision, I should think. The better of two evils.”

“Jamie used to sneak back in to visit me, and one day a couple of years later, when I was sixteen, he brought Duncan, who was eighteen at the time. I was at a low point then, despondent, listless. I had been ever since I lost Tess, because I blamed myself for not having been able to save her. Duncan… he was like this shining god, beautiful, charming, utterly magnetic. He made me feel beautiful. He made me feel worthwhile. And he gave me a way to escape from the poor house without ending up walking the streets. He asked me to marry him just a month and a half after meeting me. I was thrilled. I thought my trials were over,” she said, a bitter edge creeping into her voice.

“I take it he wasn’t the savior you’d thought he would be.”

“He wasn’t–isn’t–a monster, but he was just a small-time thief, like Jamie.” And like her, eventually, though it had been Duncan who’d coerced her into it. “And he was an ugly drunk, very ugly.”

It was clear from Viola’s expression that she knew what Nell meant by that.

“We’d been married about two years when I found out he’d robbed a jewelry store at gunpoint and brutalized the owner, and that the police were looking for him. I’d had enough. I told him I was leaving him. He… he attacked me, savagely. He used a knife on me.”

Viola flinched. “That little scar near your eyebrow…”

“That’s the least of it. The rest are in places no one can see.” Except for Will, who’d seen them for the first time that night before he left for France last month. Stay, she’d whispered as he’d lain in her bed, having come there to soothe her despair, and his, over his imminent departure for a war that might keep them apart for years, or even forever.

He hesitated, knowing, as Nell did, that this would be opening a door that could never be closed. But then he crushed her to him with trembling arms, and it was so painfully sweet, so fierce, so tender, so perfect, that the very memory of it made her heart quiver in her chest, her eyes sting hotly.

Bloody hell, he’d said as he lowered her night shift off her left shoulder, revealing the nine-inch scar that crawled in a pale ribbon from the outer edge of her collarbone down the side of her breast. Touching his lips to it, he’d whispered, I wish to God I’d met you before he did. I wish… I wish…

I know. Me, too.

“If you don’t mind my saying so,” Viola said, “Duncan sounds like a monster, having done that to you.”

“And yet he also made a very noble sacrifice once that probably saved my life. But as grateful as I am for that, I can never forget what he took from me. You see, I was with child when Duncan… did that to me. I miscarried. It was an incomplete miscarriage, but I didn’t realize that until I was reeling with fever from the infection. My landlady brought me to Dr. Greaves. He saved my life and took me in. I owe him a great deal.”

Nell considered and swiftly rejected the notion of admitting to Viola the full extent of her relationship with Cyril Greaves. Gratitude had drawn her to his bed the first time, but after that it had been about other things–comfort, affection, their mutual loneliness. Although of different religions, they’d shared the same values, including a respect for the sanctity of marital vows–ironic, given that they were both married, albeit to spouses with whom they knew they would never again cohabit. During the three years they’d slept together, Nell had refused, on religious grounds, to let him use a French letter, despite which she had never conceived. She’d taken this as proof–they both had–that she’d been rendered barren by the infection that had ravaged her after the miscarriage.

“I like Cyril,” Viola said.

“He’s a very likable man.”

“Duncan was convicted and sent to prison, I take it?”

“For thirty years.”

“I don’t suppose you’ve considered divorce. Even with the stigma, it strikes me as a more acceptable prospect than spending the rest of your life bound in wedlock to someone like that.”

“When I was a practicing Catholic,” Nell said, “it was a futile option. The only reason to divorce Duncan would have been to remarry, and if I’d done that, I would have been excommunicated.”

“But now?” Viola said.

“I went to speak to Duncan last month. That was the purpose of my trip to the prison, the one Skinner wrote about. I told Duncan I wanted a divorce, and he flew into a rage. He says I’m all he’s got, and that a marriage in the Church can never be undone. He threatened to write to you and Mr. Hewitt and tell you about our marriage if I went forward with the divorce. I was afraid if he did that, Mr. Hewitt would insist on dismissing me even if you felt otherwise. In a choice between getting that divorce and losing Gracie… well, I had no choice.”

“Right, well, it would appear that Mr. Skinner has beaten Duncan to the punch as regards the tell-all letter, and as you can see, your position with us is in no jeopardy.”

“Only because you happened to see Skinner’s letter before Mr. Hewitt did. If Duncan writes, who’s to say–“

“I shall make an effort to get to the mail before Mr. Hewitt does. It shouldn’t be too difficult, even after we return to Boston–he’s at India Wharf or the mill six days a week. So you see?” Viola spread her hands, smiling. “There’s nothing to stop you petitioning for a divorce, if that’s what you really want.”

“It is,” she said. “Desperately. I know it’s a grueling and expensive process, but I’ll do whatever I have to do. And I’ve saved a good deal of money over the years. I’m hopeful it will be enough to–“

“I’ll pay for it,” Viola said with a careless wave of her hand. “You shouldn’t have to–“

“I’m paying for it, Mrs. Hewitt. It’s a kind offer, but I think you’ve done enough for me, and I have quite a bit saved up, almost five thousand dollars.”

With a startled little laugh, Viola said, “How on earth did you manage to put away that much?”

“Given that I don’t have to pay for housing or food, it really wasn’t very difficult. I’m not in the habit of spending money, so I just put it in the bank instead, and let it earn interest. Do you think five thousand will cover the legal fees?”

“I should certainly hope so. As for it being a grueling process, you’re right, it can take a very long time and a great deal of effort–or not. Do you recall my friend Libby Wentworth from church? She was granted her divorce decree within days of filing the petition.”

“Within days?”

“It should come as no surprise to you that in the matter of divorce, as in so many other things, wealth and influence can go far toward smoothing the way. There are strings that can be pulled, corners that can be cut…”

“Money that can change hands?”

“Would you balk at that?”

“No.” Nell had far too much at stake to indulge in such qualms.

Viola said, “Libby was represented by our mutual friend Silas Mead. Silas is one of the most powerful lawyers in Boston. They call him The Magician. I seem to recall that he and his wife have expressed an interest in this area of the Cape, what with it becoming such a fashionable summer destination now that one can get here by train. Why don’t I invite them to spend this weekend with us? They can come down on the Friday train with August and Harry and Cecilia. I’ll ask Silas to be prepared to meet with the two of us on a confidential legal matter.”

“That would be wonderful,” Nell said. “But if Mr. Hewitt were to find out why you invited them…”

“Silas is nothing if not discreet. If I ask him not to mention it to Mr. Hewitt, he won’t. Meanwhile, I don’t want you fretting about all this. You’ve lost your brother. That’s enough of a burden. And I want you taking care of yourself. You’ve been looking so wan lately, and I know it’s not just the heat. I think it’s because you haven’t been eating enough. I know you can’t be trying to lose weight, a slender thing like you.”

“Hardly. I just haven’t had much of an appetite lately.”

“That can happen in the summer.”

Or in the initial weeks of pregnancy, thought Nell.