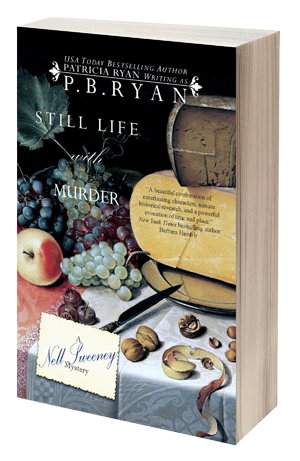

Excerpt: Still Life With Murder

Book 1: Nell Sweeney Mysteries

February 1868: Boston

It was a shocking turn of events, both wondrous and devastating; a miracle or a tragedy, depending on how you looked at it.

The news came while Nell was relaxing in the Hewitts’ music room, listening to Martin sing his new hymn for his parents. Accompanying him on the gleaming Steinway in the corner was Viola Hewitt in her downstairs Merlin chair, one of four she kept on different floors of the Italianate mansion that overlooked Boston Common from the corner of Tremont and West Streets. August Hewitt lounged in his leather wing chair by the popping fire, arms folded, spectacles low on his nose, his Putnam’s Monthly lying open on crossed legs. Nothing pleased him more on a Sunday afternoon than to bask in the bosom of his family circle in this richly formal room, his favorite. The Oriental-influenced Red Room, a silken refuge visible through an arched doorway flanked by six-foot stone obelisks, was his wife’s preferred sanctuary.

Ancestral portraits lined the music room’s rosewood paneled walls, six generations of Hewitt “codfish aristocracy,” most of them in the shipping trade; copper and cloth had gone to China, ice to the West Indies and rum to slave-rich Africa on ships that came back laden with silks, teas, porcelains, sugar, cocoa, tobacco, and the molasses with which to make more rum. But the real merchant prince among the bunch had been Mr. Hewitt’s father, scowling down from above the black marble fireplace, who’d diversified into the textile trade by founding Hewitt Mills and Dye Works, thus greatly augmenting the family fortune.

And then, of course, there was August Hewitt himself, represented by his wife’s monumental full length portrait–flanked by modestly draped, life-size statues of Artemis and Athena–who had negotiated a lucrative contract to produce U.S. Army uniforms back when almost no one seriously envisioned a war between the states. His foresight had heaped the family coffers to overflowing.

Little Grace, in her favorite apple green frock and pinafore, lay curled up on Nell’s lap, two middle fingers still somehow firmly lodged in a mouth gone lax with sleep. The grosgrain bow adorning the child’s dark hair tickled Nell’s chin, but not unpleasantly. Gracie’s somnolent breathing, the lulling weight of her, her soapy-sweet little-girl scent, all filled Nell with a sense of utter well-being.

Across the room, Miss Edna Parrish sat propped up with pillows in her favorite parlor rocker–head back, eyes closed, mouth gaping, archaic mobcap slightly askew–looking for all the world like a strangely withered baby bird. Gracie had climbed out of her nursemaid’s lap at the first wheezy snore and clambered up onto Nell’s, dozing off almost instantly.

Through the velvet-swagged windows flanking the fireplace, Nell watched snow float down out of a pewter sky, her book–Miss Ravenel’s Conversion from Secession to Loyalty by Mr. DeForest–neglected in her hand. She loved watching snow lay its glittering blanket over the city–so opaque, so pristine, as if absolving the streets beneath of their years of grime.

Boston had been a shock to her upon her arrival here three years ago–so huge, so raucous, a buzzing hive in which she’d felt not just lost but utterly invisible. How she’d longed for the rustic familiarity of Cape Cod–at first. Over time, the city gradually lost its daunting newness and began to feel like home–her home. Just as she became a part of Boston, so she became a part of the Hewitt family. Gracie was the child of her heart, if not her womb, and time had only served to cement her sense of kinship with Viola Hewitt.

That kinship notwithstanding, it was rare that Nell joined the family for these Sunday afternoon gatherings, Viola having exempted her from her duties for the better part of every weekend. On Saturdays, she often prowled the Public Library, the Lecture Hall, or–her favorite–the Natural History Museum. There were several other Colonnade Row governesses with whom she’d struck up an acquaintance as their charges played together in the Common, and from time to time they would meet for Saturday luncheon or a lingering afternoon tea–but as Nell had little in common with them, no true friendships ever sprang from these outings.

Every Sunday morning, Nell went to early Mass, a too-brief low Mass for which she had to awaken and dress in the predawn gloom, so that she would be free to watch Gracie while Nurse Parrish and the Hewitts attended services at King’s Chapel. After that, she was once more at liberty to go her own way. If the afternoon was mild, she might take a long walk–even in wintertime if the sun was bright–or perhaps settle down with a book on a bench in the Public Garden. When the weather was less agreeable, as today, she often read or drew in her room. She would be there now had Viola not specifically requested her presence today.

Gracie is better behaved with you than with Nurse Parrish, Viola had told her, and you know how Mr. Hewitt gets when she starts fussing. He’ll send her to the nursery if she makes so much as a peep, and I so long for her company this afternoon. You’ll be home anyway, because of the weather. Please say you’ll sit with us.

Unable to refuse much of anything to Viola, who’d come to hold as dear a place in her heart as her own long-departed mother, Nell had agreed. Mr. Hewitt had cast a swift, jaundiced glance at Gracie when she abandoned Nurse Parrish’s lap for Nell’s, but otherwise ignored her–as he did her governess.

Nell tried to recall the last time she and Mr. Hewitt had occupied the same room, and couldn’t. That their paths rarely crossed was due to his distaste for children in general and–from all appearances, although it made little sense–to Gracie in particular. At his insistence, the child took all her meals, with the exception of Christmas and Easter dinners, in the nursery with Nell. On weekdays he put in long hours at his shipping office near the wharves, dined at home with his wife and Martin–Harry almost always ate elsewhere–then spent the remainder of the evening at his club. He came and went on the weekends, as did Nell; on those rare occasions when they passed each other in the hall, they merely nodded and continued on their way.

“It’s different,” Mr. Hewitt concluded when the hymn ended. “Not bad, actually, but that bit about God bestowing his grace on all the sons of man, welcoming them into his arms and what not… You might think about rephrasing that.”

Martin, standing by the piano, regarded his father with a solemn intensity that might be interpreted by someone who didn’t know him well as simple filial deference. At a quick glance, the flaxen-haired, smooth-skinned Martin looked younger than his twenty-one years; it was those eyes, and the depth of discernment in them, that lent him the aspect of an older, wiser man.

His mother closed the piano softly, not looking at either her husband or her youngest son.

From the front of the house came two thwacks of the door knocker. Nell heard Hodges’s purposefully hushed footsteps traverse the considerable length of the marble-floored center hall; a faint squeak of hinges; low male voices.

In the absence of a response from his son, Hewitt said, “It’s just that one could interpret ‘all the sons of man’ as encompassing, say, the Jew, or the Chinaman. Edging awfully close to Unitarianism there.”

Long seconds passed, with Martin studying his father in that quietly grave way of his. “Thank you, sir. I’ll give it some thought.” His gaze flicked almost imperceptibly toward Nell.

A soft knock drew their attention to the open doorway, in which Hodges stood holding a calling card on a silver salver. “For you, sir.”

Motioning the elderly butler into the room, Mr. Hewitt snatched up the card. “It’s Leo Thorpe. Dear, weren’t you just saying we hadn’t seen the Thorpes in far too long? Show him in, Hodges.”

Just as August Hewitt looked to have been chiseled from translucent white alabaster, his friend Leo Thorpe could have been molded out of a great lump of pinkish clay. Florid and thickset, with snowy, well-oiled hair, his usual greeting was a jovial “How the devil are you?” Not today.

“Ah.” Mr. Thorpe hesitated on the threshold, looking unaccountably ill at ease as he took them all in. “I didn’t realize you were with…”

“I was just leaving.” Martin offered his hand to the older man as he exited the room. “Good to see you, sir.”

Mr. Thorpe dismissed the sleeping nursemaid with a fleeting glance before turning his attention to Nell. Rather than rising from her chair, and thereby waking Gracie, she simply cast her gaze toward her open book, as if too absorbed in it to take much note of anything else. He hesitated, then looked away: the governess tucked back in the corner with her sleeping charge.

Nell didn’t mind, having become adept not so much at mingling with Brahmin society as dissolving into it. Dr. Greaves was right: It could work to one’s advantage for people to forget you were there. The formal calls and luncheons to which she often accompanied Viola Hewitt, with or without Gracie–Mrs. Bouchard having little tolerance for them and Viola needing help getting about–afforded, despite their tedium, the most remarkable revelations. Nell had innumerable sketches upstairs of fashionably dressed ladies and gentlemen whispering together over their fans, their champagne flutes, their tea cups. They hardly ever whispered as softly as they should.

“Leo,” Viola began, “we were just saying it’s been far too long since we’ve had you and Eugenia over.”

“Hm? Oh, yes. Quite.”

“Why don’t you join us for dinner Saturday? Ask Eugenia to call on me some morning this week, and we’ll work out the details.”

“Yes. Yes,” he said distractedly. “I, er… That sounds splendid.”

“Everything all right, Thorpe?” inquired Mr. Hewitt. “It isn’t your gout acting up again, I hope. Here–have a seat.”

Viola offered her guest tea, “or perhaps something stronger,” but he shook his head. “This isn’t really a social call, although I dearly wish it were. It’s about…well, your son.” Thorpe fiddled with the brim of his top hat, upended on his knee with his gloves inside. “But you see, Hewitt, I was actually hoping we could speak in private.”

Viola’s smile was of the long-suffering but taking-it-well variety. “You can talk in front of me, Leo. What mischief has Harry gotten himself into this time?” As August Hewitt’s longtime confidant and personal attorney, Leo Thorpe had been most accommodating, over the years, in sweeping the worst of Harry’s libertine excesses under the carpet. Mr. Thorpe was also, as of the last city election, a member of Boston’s Board of Alderman, and thus responsible, along with the mayor and members of the Common Council, for all facets of the municipal government.

“Not another row over a woman, I hope,” said Mr. Hewitt. “It was awfully late when he came in last night–or rather, this morning. Heard him crash into something down here, so I got up to check on him. Found him reeling drunk, of course, and he’d lost his new cashmere coat and scarf somewhere–or had them stolen off him, or gambled them away. Slept through church, as usual. Had a bath drawn around noon, and his breakfast tray brought up to him while he soaked in it–must have spent over an hour in there.”

“It’s not about Harry.” Rubbing the back of his neck, Mr. Thorpe informed his hostess that he would perhaps, after all, appreciate a nice, stiff whiskey.

She rang for it. “You can’t mean that our Martin has done something…?”

“Absurd.” Her husband banished the notion with a wave of his hand.

“I couldn’t imagine it,” the alderman agreed.

“We only have the two sons, Thorpe,” Hewitt said. His wife fingered the primitive turquoise necklace half-buried in the froth of blond lace at her throat, her mouth set in a bleak line.

Thorpe looked toward the doorway as if hoping the drinks tray had materialized there.

“If it wasn’t Martin or Harry…” Hewitt persisted.

“A man was arrested last night on Purchase Street in the Fort Hill district, outside a place known as Flynn’s. It’s a…well, it’s a sort of boardinghouse for sailors, among…” his gaze slid toward Viola “…other things. Gave his name as William Touchette. That’s how they–“

“Touchette?” Viola sat up straight. Her French pronunciation was a good deal better than Mr. Thorpe’s. She looked away when her husband cast her a quizzical glance.

“That’s right,” Thorpe said. “So that’s the name they booked him under at the station house, but then this morning, when the shift changed, he was recognized by one of the day boys–Johnston, a veteran.” He took a deep breath, eyeing the couple warily. “Please understand–it came as a shock to me, too. He’s William–your son William.”

The Hewitts gaped at him.

“Seems Johnston hauled him in back in July of fifty-three,” Thorpe explained, “along with almost a hundred others, when they raided those North End bawd–” he glanced at Viola “…houses of ill fame. That’s how he knew him.”

Finding his voice, Hewitt said, “That…that was fifteen years ago. How could he possibly re–“

“He remembers the raid because it was the biggest one they ever staged, next to St. Ann Street in fifty-one. And he remembers your son because, well…he was a Hewitt.”

Viola stared at nothing, as if in a trance. “Will was home for the summer, and we hadn’t left for the Cape yet. It was the day after his eighteenth birthday. He’d gone out for the evening with Robbie. Your Jack was probably with them, too,” she told Leo. “But Robbie came home without him around midnight…”

“Impossible,” declared Mr. Hewitt. “Must just be some passing resemblance. William is dead.”

Dennis, one of the Hewitts’ two handsome young blue-liveried footmen, came with the drinks, which he offered, unsurprisingly, to everyone but Nell. Had Viola noticed, she would have said something, as she invariably did when Nell was slighted by one of the staff. Governesses, because they were often treated more like family members than employees, tended to draw the wrath of a household’s domestic staff; but at least most of them had been born into privilege and were therefore nominally deserving of a show of respect. Not so with Nell, who was widely scorned by servants with similar working class backgrounds who regarded themselves as her equals–or, in some cases, her betters–and resented having to serve her. Particularly disdainful were Mrs. Mott, Dennis, Mr. Hewitt’s valet and most of the maids–especially the sullen Mary Agnes.

Thorpe took his whiskey neat and swallowed it in two gulps. “Captain Baxter–he’s in charge of Division Two, which covers Fort Hill–he sent for me this morning, because of, well, who you are, and knowing I’m your attorney–and your friend. I went down to the station house and saw him. August, it’s William–your William.”

“He’s alive,” Viola said tremulously. “I don’t believe it.”

“I can’t believe it,” insisted her husband. “If he’s alive, why is he only surfacing now? Why did he never let us know? And why on earth would he be listed on the Andersonville death roll? It says right there he died of dysentery on August ninth, eighteen sixty-four. Why would it say that if it weren’t true?”

“I asked him that,” said Thorpe. “I asked him a great many things, but he wasn’t what you’d call forthcoming. If you don’t mind my bringing this up, has anyone gone to the prisoners’ graveyard at Andersonville and seen his–“

“Robbie has his own grave,” Hewitt replied. “As for William…” He glanced at his wife. “It seems there were a great many prisoner fatalities on that particular day. He was interred in a mass grave.”

“Cursed business,” Thorpe muttered.

“I would assume, Thorpe, that you asked this fellow point blank if he was William Hewitt.”

“Certainly–just to make it official. He wouldn’t answer, but I knew it was him. He’s a surgeon, yes?” Thorpe reached into his coat for something swathed in a handkerchief. Unwrapping it, he revealed a strip of tortoiseshell with a crack in it.

Viola sucked in a breath as he unfolded from the object a slender, curved blade stained with something dark. Nell craned her neck slightly for a better view.

Turning it this way and that, Thorpe said, “I gather it’s some sort of folding surgical knife.”

“A bistoury,” Nell said.

Thorpe turned and blinked at her.

She scolded herself for calling attention to her presence, but the damage was done. “Bistouries are surgical knives that are quite narrow,” she explained, “and sometimes curved, like that one. And very sharp at the tip.” Gracie stirred, but settled back down when Nell rubbed her back.

“It’s obviously a well-used blade,” Thorpe said, “but he’s kept it honed. The blade is stamped ‘Tiemann.'”

“That’s the manufacturer,” said Viola. “That bistoury is part of a pocket surgery kit I gave Will for Christmas when he came home that last…well, it was his last Christmas with us, in sixty-three. He and Robbie were both granted two-week furloughs. Robbie was with us the whole time, but Will only stayed two days. The last time I spoke to him was Christmas night, as he was heading up for bed. The next morning, he was gone. I never saw him again.”

“A pocket surgery kit?” Thorpe said.

“Yes, it was this little leather roll with the instruments tucked inside. He had his full-size kit, of course, but I thought a portable set might come in handy. Where did you get that?”

“From the policeman who arrested your son. William…” Wrapping the bistoury back up, he said, “I’m sorry, Viola. William used it to cut a man’s throat.”

Color leeched from her face. Her husband sat back, slid off his spectacles, rubbed the bridge of his nose.

The alderman poured himself another whiskey. “Your son–or rather, William Touchette–has been formally charged with murder. He killed a merchant seaman in an alley next to the boardinghouse late last night. Fellow by the name of Ernest Tulley.”

“No,” Viola said dazedly. “No. I don’t believe it. Why on earth would he do such a thing?”

“He wouldn’t say, even after the boys…well, they, uh, interrogated him at some length last night, but he wasn’t talking. As near as they can figure, it was a frenzy of intoxication. The other sailors say he’d come there to smoke opium. There’s a room set aside for–“

“Opium?” She shook her head. “My Will…he would never…” Her normally throaty voice grew shrill. “He’s a surgeon, for God’s sake! August, tell him.” She pounded the arms of her wheelchair. “Tell him! Will could never–“

“Viola…” Her husband rose and went to her.

“Tell him,” she implored, clutching his coat sleeve. “Please, August.”

Nell stared, dumbfounded. Never in the three years she’d known Viola Hewitt had she seen her lose her composure, even for a moment.

“Viola, I’ll take care of–“

“There’s been some horrible mistake,” she told Thorpe in the strained voice of someone struggling to get herself in hand. “I know my Will. He…he was always…spirited, but he could never take a life. He’s a healer. Leo, please…”

Her husband took her by the shoulders, gentling his voice. “Do you trust me, Viola?”

“You know he didn’t do this, don’t you?”

“You must get hold of yourself, my dear. Giving vent to one’s emotions merely makes them more obdurate–you know that. Now, I’m going to take Leo upstairs, to the library, to sort this thing–“

“No. No! Stay here. I’ll stay calm. I’ll–“

“You’ve too delicate a disposition for such matters, my dear. I’ll take care of everything, but I must caution you not to make mention of this to anyone–and that includes Martin and Harry.”

“I can’t tell them their own brother is alive? And arrested for murder? For heaven’s sake, August, they’ll find out sooner or later.”

“Just trust me, Viola. Thorpe.” Hewitt motioned his friend to follow as he left the room.

“August!” she cried as the two men headed for the curved stairway that led from the back end of the center hall to the upper floors. “What do you mean, you’re going to ‘take care of everything’? What does that mean, August?”

“Mrs. Hewitt…” Nell began.

“I’ve got to get upstairs,” she said in a quavering voice as she grabbed the folding canes off the back of her chair. “Where’s Mrs. Bouchard?”

“It’s Sunday. She’s got the day–“

“You help me, then.” Yanking the canes open, she planted them on the Oriental rug. “Hurry!”

“Ma’am…” Nell looked from the sleeping child in her arms toward the ceiling, where footsteps squeaked; the library was directly overhead, right off the second floor landing.

“You’re right. By the time I got up there… You go!”

“Me? They’ll never let me–“

“Tiptoe upstairs and listen outside the door.”

“Eavesdrop?”

“Just don’t let anyone see you. Be on the lookout for Mrs. Mott. She can be quiet as death, that one.”

“Mrs. Hewitt, your husband will dismiss me for sure if he catches me.” He’d sacked employees for far less.

“He won’t if I make enough of a fuss. You know he can’t bear to distress me. Nell, please.” Tears trembled in Viola’s eyes. “I’m pleading with you. I’ve got to find out what he’s planning to do. I’m so afraid… Please.” Plucking a lace-edged handkerchief from her sleeve, she blotted her eyes and held out her arms. “I’ll take Gracie. Hurry!”

Gracie mewed like a vexed kitten when Nell rose and carried her across the room. “No…” the child griped sleepily, no doubt assuming she was being taken upstairs to finish her nap in the nursery. “Want Miseeney.” She jammed those two fingers in her mouth, eyes half-closed, pinkened right cheek imprinted from the double row of tiny covered buttons on Nell’s bodice.

“Miseeney has to go now,” Nell said softly as she tucked the child in her adoptive mother’s lap. “Nana will hold you.” Having Gracie call her “Nana” had been Viola’s idea; it would inspire too many raised eyebrows in public, she reasoned, for such a young child to call a woman of her advanced years “Mama.”

Nell stole upstairs as quietly as she could, thankful for the carpeted stairs and the plush Aubusson on the landing. Muffled voices grew louder as she neared the closed library door, where she paused, sketched a swift sign of the cross. Please, St. Dismas, please, please, please don’t let him open that door and find me lurking here. Funny how she still directed her prayers to the patron saint of thieves, after all these years.

“He could hang for this, you know.” Leo Thorpe.

“Has he been arraigned yet?” asked Hewitt.

“Yes, and he was utterly uncooperative. Waived his right to counsel, made no attempt to defend himself. Refused to plead, so the court entered a not guilty plea on his behalf. He did ask for bail, though, and I understand he seemed quite put out when it was denied, as is customary in cases that warrant the death penalty. He’ll be detained until trial.”

Hewitt grunted. “Arrogant bastard didn’t think he needed a lawyer. Serves him right.”

“Of course…given your position and influence, if you were of a mind to get the bail decision overturned…”

“I’m not about to grease some judge’s palm just so that damnable blackguard can be free to cut some other poor bastard’s throat.”

This was the first time Nell had ever heard coarse language spoken in this house. She would not have expected it from the rigidly proper August Hewitt, even with no ladies present.

“Are you…quite sure, old chap? He is, after all, your son. I mean, I appreciate that you’re less than sympathetic right now, but given time to reflect–“

“Not one red cent. Damn him,” Hewitt said shakily. “Damn him for doing this to his mother. To go three years–over three years–without letting us know he was alive, and then this…this… By Jove, he committed murder! If he was innocent, he would have pled not guilty right from the start. And opium? He was always a bad egg. Sad to say, but even as a little child, I knew he would come to no good.”

“Heartbreaking, when they’re born that way.”

“Of course, Viola is soft-hearted when it comes to William. Understandable. He’s her firstborn, and women are sentimental creatures.”

“Quite.”

“What address did he give?” Hewitt asked.

“Some hotel. He doesn’t have a permanent address.”

“Well, not here in Boston, but surely–“

“Anywhere. He appears to be something of a nomad.”

“A Hewitt wandering around homeless. Never thought I’d see the day.”

“Say, Hewitt,” Mr. Thorpe began, “is it true you’ve got a bottle of hundred-year-old cognac locked up in that cabinet?”

“It is, but you’re daft if you think you’re getting any. It’s the last of a case my grandfather bought from Hennessy’s first shipment to New York in seventeen ninety-four, and I’m saving it for the birth of my first grandchild. There’s a nice tawny port in that decanter–help yourself.”

“I do believe I will.”

“Cigar?”

“Capital!”

In the ensuing silence, Nell perused the paintings hung close together on the darkly paneled walls–Mrs. Hewitt’s portraits of her family, bordered in ornate gilt frames. Here on the landing there was one of her husband with his three younger sons and several of those sons posing separately and in pairs. Achingly handsome men, in particular the late Robbie, with his thick, gilded hair and dramatic black eyebrows. Around the corner, in the corridor leading to the family bedrooms, were many more of her paintings, most of the Hewitt scions ranging in age from infancy through their twenties. Notably absent from the collection was any depiction of their eldest son. All Nell really knew about William Hewitt was that he’d been schooled, from early childhood, in Great Britain.

Hewitt’s voice penetrated the thick oak door again. “There was always a William Problem, from the moment he was born. I must say, Viola handled his youthful misdeeds with remarkable aplomb, but this… He’s gone too far. I won’t have her exposed to him. Her health’s been fragile, you know, ever since she fell ill in Europe. I don’t think she could endure the strain, if I were to let William back in her life–not with what he’s become.”

“Damn fine cigar,” Thorpe muttered.

“Rest assured, Thorpe, it is my intent that William be prosecuted to the fullest extent possible–but under this assumed name, mind you. What is it, again? Something French.”

“Touchette,” Thorpe replied, still mispronouncing it. “But won’t he be recognized for who he really is?”

“Unlikely. William grew up in England, remember, except for summers, and he always went with us to the Cape. He actually spent very little time in Boston, and Viola could almost never get him to go calling with her, or to dinners and dances, so he met hardly anyone. Robbie was the only one he spent any time with–and your Jack, of course. Robbie wouldn’t go anywhere without him–remember?”

“Yes, quite. Oh–! Did I tell you Orville Pratt and I are bringing Jack aboard as a junior partner in the firm? We’re going to make it official when we announce Jack’s engagement to Cecilia Pratt–probably during the Pratt’s annual ball.”

“Excellent! Jack’s a fine young man–as was Robbie, despite William’s efforts to corrupt them both. But as to his being recognized, rest assured there’s not a soul in Boston–aside from Jack, I suppose–who would know him if he saw him on the street. Except, of course, for those fellows at the station house. They’re the ones who trouble me. How many are there?”

“Well, Johnston, of course–the one who remembered arresting him. He told one or two others, including Captain Baxter, and Baxter summoned me. I gave orders for no one else to be told until I could speak to you, and I had him put in his own cell, away from the other prisoners.”

“Those who know must be silenced. From what I hear, there isn’t a single member of the Boston Police Department who wouldn’t sell his mother into white slavery for the price of a pint of ale.”

Even through the door, Nell heard Thorpe’s deep sigh.

“Offer them whatever it will take for them to forget who William Touchette really is,” said Hewitt. “And of course I expect a certain zeal in bringing him to justice. Perhaps a bonus for those involved once he’s found guilty and sentenced. Have this Captain Baxter handle it. But talk to him soon, before he and the others start opening their mouths.”

“It will be done within the hour.”

“I don’t want my name mentioned, Thorpe, or yours. It goes no further than Baxter.”

“What about the girl? That pretty little governess?”

“Nell? She’s devoted to my wife. She’ll keep her mouth shut if I explain to her that it’s in Viola’s best interest–which, of course, it is, although Viola won’t see it that way. As for William, I want him out of that station house and away from prying eyes as soon as it can be arranged.”

“He’s to be transferred to the county jail on Charles Street tomorrow to await trial.”

“Good. Bury him as deep in that bloody mausoleum as you can get him.” Now it was Hewitt’s turn to sigh. “Damn him.”

“Miss Sweeney?”

Nell whirled around, her heart kicking. “Master Martin.” He’d come around the corner, evidently on his way downstairs. “I was just looking at your mother’s paintings,” she said as she walked past him, into the corridor proper, so as not to be heard by the men in the library.

“Extraordinary, aren’t they?” He looked about fifteen when he smiled like that. “I keep telling her she should hang them downstairs, where visitors can see them, but she thinks that would be vulgar.”

Taking in the myriad paintings lining the long, high-ceilinged passageway, she said, “I was wondering why there are none of your brother William.”

“I assumed you knew.” Martin shoved his hands in his trouser pockets. “He was the black sheep of the family.”

“I suppose I suspected that. No one ever talks about him.”

“Father doesn’t like to hear his name–even now that he’s gone. I find it hard to understand. I mean, he can’t have been any worse than Harry, and Harry’s always in one fix or another–either it’s his drinking, or his gambling, or his…” Martin looked away, clearly discomfited.

“His mill girls?” This from Harry himself as he emerged from his room down the hall, teeth flashing, tawny hair well brushed and gleaming. The only evidence of last night’s excesses would be his complexion, which had that bleached-out Sunday palor, and a certain puffiness around the eyes. “Say it, Martin. Our lovely Miseeney is much like mother, you know–unshockable.” Surveying Nell’s dress from neckline to hem, he said, “And doesn’t she look fetching this morning. Is that a new shade of gray?”

“Morning?” Martin scoffed. “It’s two-thirty in the afternoon, Harry. And I hardly think Miss Sweeney appreciates your mockery.”

“Miss Sweeney recognizes a good-natured jest when she hears it. Are you saying you’re the only one who’s allowed to flirt with her? Hardly seems fair.”

“I wasn’t… We weren’t…” Even in the dimly lit corridor, Nell could see Martin’s ears flare crimson.

“If he takes any liberties,” Harry told Nell as he sauntered past, “you must call me at once.” With a wink, and leaning conspiratorially close, he added, “I’d give anything to witness that.”

***

This was the first time Nell had ever seen Viola Hewitt cry. It wasn’t gentle weeping, either, but great, hoarse sobs that shook her to the bones as she sat hunched over the writing desk in her pink and gold sitting room. “It’s all my fault,” she kept wailing into her handkerchief. “All my fault…”

“Of course it’s not your fault,” Nell soothed as she kept half an eye on Gracie in her Nana’s adjacent boudoir, dragging hatboxes out of the closet while Viola’s lady’s maid, Paola Gabrielli, sat in the corner sewing a veil onto a purple velvet bonnet. “How could it be your fault?”

Viola shook her head, tears dripping onto the letter in front of her, a letter that began, Dear Will… “Oh, God. I’m a horrible mother.”

“You’re a wonderful mother.”

“No, you don’t know. You don’t know. And now…and now my baby, my Will… They’re going to h-hang him. And it’s all my fault.”

Her fault? Did she knife that man outside Flynn’s boardinghouse? Did she tell Alderman Thorpe to bury her son “as deep as you can get him” in the Charles Street Jail? There were people responsible for begetting this situation and making it worse, but it seemed to Nell that Viola Hewitt was as blameless a victim of it as Ernest Tulley.

Heedless of the tear stains dotting the letter, Viola folded it and tucked it into an envelope, on which she wrote, in her signature violet ink, Dr. William Hewitt before drawing up short. She jammed the pen back in the crystal inkwell, tore the envelope away and replaced it with a fresh one, which she addressed to Mr. William Touchette. She heated a stick of violet sealing wax in the flame of her desktop candle, melted it into a tiny silver spoon, dripped the molten wax onto the envelope’s flap and imprinted it with her monogrammed insignia.

“You must take this to Will,” she told Nell.

“What?” Nell exclaimed as her employer shoved the letter in her hand.

“You’re the only one who can do this, Nell. God knows August won’t. He won’t even acknowledge Will as a member of this family. He doesn’t care if he hangs–you told me so yourself. And he’ll be livid if I bring Martin or Harry in on this.”

“Mrs. Hewitt, I–“

“Do it this afternoon. Once they transfer him to the county jail, you’ll have a hard time gaining access to him. Right now, he’s at the Division Two station house, which is on Williams Court. I used to bring blankets and Bibles to the prisoners there. Each holding cell has a sort of anteroom for visitors. You’ll be able to talk to him without anyone overhearing you.”

“What if Mr. Hewitt sees me leave? Or Hitchens?” The devoted valet reported everything to his employer. August Hewitt would cast her out in a heartbeat if he found out she’d gone behind his back. Nell’s most harrowing nightmare–the one from which she literally awoke in a sweat from time to time–was the one where she found herself back in her old life, with no home, no family…and worst of all, no Gracie. “Won’t it look suspicious, me going out after deciding to stay home because it was snowing so hard?”

“If anyone asks, you can tell them you’re planning to paint Boston Common in the snow, and you need to see how it looks.”

It was a good lie; Nell was grudgingly impressed. But what if it didn’t work? Going behind August Hewitt’s back this way was far worse than eavesdropping at his library door. She’d never heard him sound so furious–or determined. If he found out what she’d done, he would fire her, and Viola would be helpless to prevent it. No one defied August Hewitt and got away with it, ever.

And, too, the notion of walking into a police station filled Nell with a cold dread all its own. “I don’t think I could handle this, Mrs. Hewitt.”

Misjudging the reason for her trepidation, Viola said, “Nell, believe me, you have nothing to fear from my Will. He’s incapable of doing what they say he did. And he would die before he’d let an opium pipe touch his lips. He thinks it’s a blight on humanity–he once told me so himself. He said they should outlaw it here, as they have in China. He’s a good man, a surgeon. He would never…cause you harm, if that’s what you’re thinking, or–“

“It’s not that. I just…I…”

“I need to find out what really happened, from Will himself. Obviously I can’t go myself, much as I wish I could. I’ve dreamed of seeing him again–literally. I wake up sobbing from those dreams. But I have to think of Will. If I were to visit him, everyone would notice me. They know who I am there. Someone would figure out who Will really is, and he’s obviously gone to great pains to prevent that. And, if Mr. Hewitt were to find out I’d defied him…” Her brow furrowed. “He mustn’t find out you’ve been there, either. Use a false name. Say you’re doing charitable work. Talk to Will alone if you can. Tell him I’m going to try to overturn the bail decision tomorrow so he can get out of there.”

“Can you do that? Without Mr. Hewitt finding out?”

“The husband of an acquaintance of mine is a judge in the criminal court. Horace Bacon is his name. I happen to know she likes to live beyond her means, and I’ve heard rumors Horace has accrued a fair amount of debt. I can’t see him turning down my request if it’s accompanied by a nice, fat envelope. And if it’s fat enough, I imagine you can convince him to expedite the process and keep my name off any paperwork having to do with–“

“I can convince him?”

“You’re the only one I can ask to do any of this, Nell.” Frowning, she said, “I’ll need to hire a lawyer, too.”

“Won’t the court appoint a public defender?”

“No, we need our own man, someone very good and very discreet, who’ll agree to keep Mr. Hewitt out of it. That will be trickier than the business about the bail. My husband knows just about every lawyer in Boston.”

A flurry of nonsense babbling drew Nell’s attention to the bedroom, where Gracie was gamboling in circles, arms outstretched, an ostrich-plumed bonnet jammed low over her face. Paola–Nell’s only real friend on the Hewitts’ staff–caught Nell’s eye and smiled. A darkly beautiful woman about Viola’s age, although she looked much younger, Paola was known as “Miss Gabrielli” despite being married–assuming her husband was still alive, for she hadn’t been back to Italy in the thirty or so years she’d served as Viola’s lady’s maid. By the same token, tradition regarding housekeepers dictated that Evelyn Mott, a spinster, be addressed as “Mrs. Mott.” None of it made much sense to Nell, but she’d long ago stopped trying to understand Brahmin customs.

“I can’t leave,” Nell said. “Who’ll keep an eye on Gracie?” She was a child who got into everything and needed frequent running after, which was why Viola was unequal to the task.

“Nurse Parrish will awaken from her nap soon enough. In the meantime, Paola can set aside her work long enough keep a proper watch over her. Please, please, Nell–I beseech you. I must find out what really happened last night. I won’t rest until I do.” Fresh tears pooled in her eyes. “You’re the only one I trust, and I know you can do this. You’re so strong, so clever and capable. And people respond to you. Men respond to you. You’ll have no trouble getting in to see Will.”

Nell pressed the heel of her hand to her forehead, feeling trapped and woozy and increasingly resigned. If not for Viola Hewitt, she would still be in East Falmouth, wearing frayed cast-offs as she tended round-the-clock to Cyril Greaves’s every need. Not that she’d begrudged him any of it, God knew. She’d been fond of Dr. Greaves, very much so. He’d quite literally saved her life–only to remake her into the kind of woman who could function in a world of glittering privilege. He’d let her go regretfully, but with a measure of grace that had touched Nell deeply, because she’d known he was doing it for her. For all that, she would be eternally grateful; but she was grateful to Viola Hewitt as well, exceedingly so, for having invited her into this world–and for giving her Gracie, the only child she would ever have.

In a quiet voice still rusty with tears, Viola said, “You’re lucky in a way, you know that?”

“Know it? I think about it every morning when I awaken and every night as I’m falling asleep.”

“I don’t mean that. I mean… You’re so much freer than I am, really–freer than any woman of rank. We’re all kept shrouded in cocoons of propriety lest we somehow bring scandal upon our families–and there are more ways of doing that than you can imagine. The governess, however, occupies a singular niche in our world, neither servant nor pampered gentlewoman, but something quite apart. Do you have any idea how blessed you are to be able to come and go as you please? The demands of my class have crippled me more surely than the affliction that put me in this chair. You, on the other hand, have no cocoon to bind you.”

Reaching out, Viola stroked Nell’s cheek. “You’re a butterfly. How I do envy you.”

***

“A lady to see you, Touchette,” announced the pockmarked guard through the iron-barred door of the holding cell.

“I don’t know any ladies.” The voice from within–drowsy-deep, British-accented and vaguely bored–did not belong here. It was a voice meant for the opera box, the ballroom, the polo field…not this fetid little police station cage.

Nell’s view of William Hewitt was limited by her position against the wall of the cramped visitor’s alcove and the fact that it was only the cell’s door that was comprised of open grillwork; the walls were solid brick. From her angle, all she could make out through the barred door were two long legs in fawn trousers, right ankle propped on left knee. A hand appeared and struck a match against the sole of a well-made black shoe. The hand was long-fingered, capable–a deft hand with a scalpel, she would guess.

Or a bistoury.

“Her name is Miss Chapel,” said the guard as he hung Nell’s snow-dampened coat and scarf on a hook. “She’s from the Society for the Relief of Convicts and Indigents.”

The aroma of tobacco wafted from the cell. “I don’t suppose it would do any good to point out that I am neither a convict nor an indigent.”

“You’ll be a convict soon as they can manage to drag your sorry…” the guard glanced at Nell “…drag you in front of a jury. And then you’ll be just another murdering wretch swinging from a rope over at the county jail.”

Nell clutched to her chest the scratchy woolen blanket and Bible she’d brought. She hated this. She hated being in this monstrous brick box of a building, surrounded by blue-uniformed cops who all seemed to stare at her as if they knew who she really was and why this was the last place she should be. She hated the way Gracie had cried and reached for her, squirming in Paola’s arms, as she’d put on her coat to come here. And she really hated having to confront this man who may or may not have cut another man’s throat last night in a delirium born of opium–or lunacy.

“You can give him them things, ma’am, but I’ll have to check ’em first.” The guard held his hand out. “The blanket, then the Bible.” He unfolded and shook out the former, fanned the pages of the latter, and handed them back.

“You can sit here if you’ve a mind to pray or what have you.” The guard scraped a bench away from the wall and set it up facing the iron-barred door from about five feet away. “You’d best keep your distance. If he tries anything, like grabbing you through the bars or throwing matches at you, you give me a holler–loud, ’cause I’ll be all the way down the hall.”

Matches? Nell thought about the flammable crinoline shaping her skirt, and the newspaper stories of women burned alive when their dresses brushed candles or gas jets. She stood motionless after the guard left, listening to the receding jangle of his keys as he returned to his station at the far end of the hall.

“I’ll take the blanket.” The long legs shifted; bedropes squeaked. “You can keep the Bible.”

With a steadying breath, Nell stepped away from the wall and approached the door to the cell, staying a few feet back, as the guard had advised.

Its occupant was standing now, his weight resting on one hip, drawing on a cigarette as he watched her come into view. He was tall, somewhat over six feet, with hair falling like haphazard strokes of black ink into indolent eyes. His left eyelid was swollen and discolored, with a crusted-over cut at the outer edge. Two more contusions stained his beard-darkened jaw on that side, and his lower lip was split. They interrogated him at some length last night.

Even unshaved and unshorn, his face badly beaten, there could be no mistaking that this man was Viola Hewitt’s son. It wasn’t just his coloring–the black hair and fair skin–but his height, his bearing, the patrician planes and hollows of his face.

His gaze swept over her from top to bottom as he exhaled a plume of smoke, but it felt different than when Harry did it. With Harry there was always a speculative glimmer behind the roguish audacity in his eyes, a spark of real heat that he could never fully disguise. The eyes of the man assessing her at the moment betrayed no such illicit interest. He took her measure as indifferently as if she were a mannequin in a shop window.

Nell felt like a mannequin sometimes, or a doll, given Viola Hewitt’s enthusiasm for dressing her. I’m too old and too crippled to wear the newest styles, she would tell Nell, so you must wear them for me. The dresses she ordered were always of the latest Paris fashion, but discreet in cut and color, as befitted a governess–no stripes or plaids, no swags, ruffles, bows, or rosettes, no feathered hats. Today’s costume was typical: a gunmetal day dress with the sleek new “princess” skirt and a small, front-tilted black hat. The only jewelry she wore on a regular basis was the pretty little gold pendant watch Viola had given her their first Christmas together. Just this morning, Viola has praised her “restrained elegance.” Nell didn’t think she would ever understand how rich people could interpret such dreariness as elegant.

As for William Hewitt, he might have passed for something akin to elegant this time yesterday, but now… He was in his shirtsleeves; moreover, his shirt was flecked near the top with reddish-dark stains–whether his own blood or Ernest Tulley’s, she had no way of knowing. His collar and tie were both missing, giving him a decidedly disreputable air. Adding to the effect was the cigarette, which Nell had never seen a man of his station smoke, although she’d heard they were catching on in certain fast circles.

He came toward her, hand outstretched.

She stumbled back, dropping the Bible and knocking over the bench.

He looked at her through the bars, not smiling exactly, although there was a hint of something in his eyes that might have been amusement. Idiot! Nell berated herself. She knew not to show fear around dangerous men. A man with the predatory instinct was like a wolf; if he sensed your weakness, you were done for. It was a hard lesson, but one she’d learned well. She was out of practice, that was it; too much soft living among civilized people.

He gestured toward the blanket wadded up in her arms. “I was just reaching for the–“

“Of course. I… Here.” Swallowing her trepidation, she stepped just close enough to push the blanket through the bars. The unbuttoned cuffs of his sleeves, which should have been white, were stiff and brown, as if encrusted with mud; but of course it wasn’t mud.

He took the blanket, shook it out and draped it over his shoulders, chafing his arms through it–curious, since it was quite warm in here, thanks to a wood stove out in the hall. “Good day, Miss Chapel.” He turned his back to her in brusque dismissal.

Retrieving the Bible, she stammered, “I…I actually need to–“

“Trust me when I assure you that any time spent praying over me would be quite wasted.” He crossed with a slight limp to the cot he’d been sitting on before, one of two against opposite walls of the windowless cell. Both mattresses were sunken and lumpy, their ticking soiled with a constellation of stains that didn’t bear thinking about. There was no pillow, no furniture–just an empty stone-China chamber pot in one corner and a tin bowl of gruel studded with cigarette butts in the other.

He flung his cigarette into the gruel and sat again, stiffly. Tucking the blanket around him, he leaned back against the wall, yawned and closed his eyes.

“I didn’t come here to pray over you, Dr. Hewitt,” Nell said.

If he had any reaction to her use of his real name, he kept it to himself.

“Your mother sent me,” she said.

He opened his eyes, but didn’t look at her.

“She’s brokenhearted over what’s–“

“Go away, Miss Chapel.” He shut his eyes again.

“It’s Miss Sweeney, actually.”

“Go away, Miss…” He looked at her, interest lighting his eyes for the first time since she’d arrived. It was the Irish surname, she knew. He glanced again at her fine dress, her kid gloves and chic hat–and for the first time, he really looked at her face. “Who are you?”

“My name is Nell Sweeney. I work for your mother. I gave a false name because…well, she sent me here secretly. Your father doesn’t…he doesn’t want anyone to know who you really are.”

It took a moment, but comprehension dawned. “He just wants William Touchette to be quietly tried and hanged, thus solving forever the William Problem.” When Nell didn’t deny it, he chuckled weakly, but something dark shadowed his eyes, just for a moment. “So you work for my mother, eh? As what, some sort of companion? Or are you a new nurse? Did she finally oust Mrs. Bouchard for having a backbone?”

“No, I was trained as a nurse, but it’s not what I do–Mrs. Bouchard is still there. And although I do believe your mother has come to regard me as a sort of companion, officially I’m a governess. Your parents hired me to help Nurse Parrish care for a child they adopted.”

“Adopted?” He sat up, staring at her. A bitter gust of laughter degenerated into a coughing fit. “Haven’t they ruined enough sons?” he managed as he fumbled inside his coat.

“It’s a little girl, actually. Gracie–she’s three.”

“I pity her.” Dr. Hewitt produced a small, decorative tin labeled Bull Durham, which contained pre-rolled cigarettes, and put one between his lips. “I mean, I’m sure you’re a capable governess,” he said as he lit it. In the corona of light from the match, his face had a damp, candle-wax pallor. “You strike me as a sensible woman, in spite of the knocking over of the bench. But it is my opinion that people should recognize when they’re hopeless at something, and give it up–and if there were ever two people utterly hopeless at parenting, it’s Viola and August Hewitt.”

He bundled himself in the blanket again and leaned back against the wall, coughing tiredly as he puffed on the cigarette, his face sheened with perspiration.

“Are you sick?” Nell asked.

“Not strictly speaking.”

“It’s been my observation that surgeons are ill-equipped to diagnose themselves.”

“If I were still a surgeon, I suppose that might be a consideration.”

“You’re not a surgeon anymore?”

“Christ, look at me!”

Rattled by his vehemence–and by the blasphemy, which her ears were unused to of late–Nell turned and busied herself righting the bench. She sat, smoothing her skirts just to have something to do with her hands.

“As I said, Miss Sweeney, when one is hopeless at something, the wisest course is to just give it up. Better for all concerned.”

She decided to redirect the conversation to her reasons for coming here. “Your mother really is very distraught over your arrest, Dr. Hewitt. She sent me here to…well, among other things, to find out what actually happened last night.”

He regarded her balefully. “If I didn’t tell the men who did this to me–” he pointed to his face “–why on earth would I tell you?”

“For your mother’s sake?”

A harsh burst of laughter precipitated another coughing fit. “You will have to do much, much better than that, Miss Sweeney.”

Why, oh why couldn’t Viola have found someone else to do this? Changing tack, Nell said, “She intends to hire an attorney to represent you.”

“A singularly idiotic notion.”

“I beg your pardon?”

He covered another yawn with the hand holding the cigarette, which was quivering, she noticed. “Why waste the fellow’s time?”

“A rather nihilistic outlook, considering your life is at stake.”

“Nihilistic?” Dr. Hewitt regarded her with amused incredulity. “Where the devil does a girl like you learn about nihilism?“

Nell sat a little straighter, spine and corset stays aligned in stiff indignation. “It isn’t only surgeons who learn to read, Dr. Hewitt. The writings of the German philosopher Heinrich Jacobi–“

“Yes, I’m familiar with his work–it was assigned to me when I was reading philosophy at Oxford. What I’m wondering is why you read it.”

“The physician I was apprenticed to–the one who trained me in nursing–he took it upon himself to tutor me in various disciplines.”

“Did he, now.” Before Nell could ponder what he meant by that, he said, “What’s this fellow’s name? I know most of the physicians in the city, at least by reputation.”

“He lives on Cape Cod, near your parents’ summer cottage in Waquoit. His name is Cyril Greaves.”

“Is that where you’re from, then? Waquoit?”

“Near there–East Falmouth. Dr. Hewitt, I didn’t come here to talk about myself.”

“Yet I find you suddenly fascinating, given your unexpected dimensions, and I’ve been so frightfully bored. Was he an older man, this Dr. Greaves, or…”

“Forty-four when I left his employ.”

“Not that old, then. How long were you apprenticed to him?”

“Four years, starting when I was eighteen.”

“And before that?”

Nell lifted the Bible from the bench next to her and placed it on her lap like a talisman, all too aware of how defensive she looked. “I’m afraid I don’t really see the point of–“

“Indulge me. I’ve been quite starved for conversation in this place.” He took a thoughtful pull on his cigarette. “You had a family, presumably. Parents? Brothers and sisters? What did your father do?”

What didn’t he do? “He worked on the docks, mostly–cutting fish, unloading ships, that sort of thing.”

“A day laborer, was he?” The lowest of the low, taking whatever job was available for whatever pittance was offered.

“That’s right,” Nell answered with a carefully neutral expression.

“A hard life, I daresay.”

“You’ve no idea.” Nell had the disquieting sense, as he questioned her, that he was slipping an exploratory scalpel into her mind, her memories, her very self–a dangerous proposition, given what he might unearth if he ventured deeply enough. Too much was at stake–far too much–for her to permit that.

She said, “Let me save us some time here, if I may. I had a family. They’re gone now. The details are really none of your concern. I’m sorry if you’re bored because you’ve ended up here after taking your wonderful life with all of its blessings and tossing it in the trash bin. That was your choice to make, though, and I hardly think it should now be my responsibility to provide jailhouse entertainment for you at the expense of my privacy.”

Sticking the cigarette in his mouth, Dr. Hewitt clapped listlessly. “What a very impassioned speech, Miss Sweeney. Have you ever considered the stage as a vocation?”

She looked away, disgusted.

“No? I suppose I’m not surprised. Actresses have to be willing to bare their souls–and somewhat more than that, from time to time.” His gaze skimmed down to the knifelike toes of her black morocco boots, just visible beneath the hem of her skirt, and back up. “If there was ever a woman buttoned up more snugly than you, I’ve yet to meet her.”

“Must you keep turning the conversation back to me?” she asked.

“And yet I sense, if you loosened just one or two of those buttons, the most extraordinary revelations would burst forth. That’s the last thing you want, though, isn’t it? To be exposed. It terrifies you.”

“As I said,” Nell continued tightly, “your mother plans on hiring a lawyer to–“

“Go away.” Sitting up, he hurled the cigarette into the bowl of gruel, where it sizzled, and tugged his blanket more tightly around himself. “Just go away, if that’s all you can prattle on about. And tell Lady Viola to abandon this foolish notion of getting a lawyer. Some people are meant to hang.”

“Guilty people are meant to hang.”

“Precisely.” Sweat trickled into his eyes; he wiped it away with the blanket. “Not that I’m too keen on that particular method of execution. I saw six men hanged at the same time once. It took a full ten minutes for them to stop writhing. One of them broke his neck, but he still struggled. Hellish way to go. I wouldn’t mind a firing squad–or perhaps a syringe full of morphine. Quick, fairly painless…”

“Are you saying you killed that man?”

“Boorishly put, Miss Sweeney. You’re cleverer than that.”

“Your mother believes in your innocence, Dr. Hewitt.”

“Why, for God’s sake?”

“Because you’re her son,” Nell said quietly. “Because she loves you. Why else would she have sent me here?”

He laughed wheezily, and without humor. “Because she’s addicted to philanthropic projects–it helps to ease her remorse over her lack of a soul. Trust me when I tell you that woman is incapable of maternal love. You think you know my parents, Miss Sweeney, but you really have no idea.”

Rising from the bench, Nell retrieved Viola’s letter from the petit-point chatelaine bag hanging from her waistband–a practical alternative to a mesh reticule–and reached through the bars to hand it to Dr. Hewitt. “She asked me to give this to you.”

“Still using the violet ink, I see.” Turning the envelope over, he rubbed his thumb across the dab of sealing wax. “She always did like to do things handsomely.” He crushed the letter in his fist and tossed it into the chamber pot.

Gasping in outrage, Nell clutched the iron bars that separated them. “Your mother wept as she wrote that,” she said with jittery fury, feeling close to tears herself on Viola’s behalf. “She sobbed. And you just…” She shook her head, appalled at the sight of the crumpled-up letter in the stoneware pot. “Then again, I don’t know what else I would expect from a man who would walk away from his own family–his own mother–at Christmas, without even saying goodbye. Not to mention letting them think you’ve been dead all this time. It’s you who’ve lost your soul, Dr. Hewitt, and I pity you for it, but I despise you, too, for bringing this grief upon a woman who’s shown you nothing but a mother’s true, heartfelt love. Perhaps you really do deserve to hang.”

Uncoiling from the cot, he closed the distance between them with one long stride, the blanket slipping to the floor. Tempted to back away, Nell held her ground, hands fisted around the bars, not flinching from his gaze. For a moment he just stared down at her with his bloodied shirt and battered face, eyes seething, a hard thrust to his jaw. Reaching inside his coat, he produced a match, which he scraped across one of the iron bars; it flamed with a crackling hiss.

“You were told to keep your distance,” he said softly.